Did the UNFCCC review process improve the national GHG inventory submissions?

Abstract

The Parties to the Climate Convention have set up an elaborate system of reporting and review with a view that each Party informs all other Parties on the progress made towards the targets of the convention. In this paper we analyze the annual national emission inventory submissions from Parties with quantified emissions reduction targets under the Convention or under the Kyoto Protocol (so-called Annex I Parties), both with respect to the effort needed for the review and the resulting changes in the reported emissions. Expert review teams and the Convention’s secretariat invest about 4000 working days each year to run the reviews. About one quarter of this is needed for the secretariat.

Although estimates for emissions differ between successive inventory submissions, these differences remain for a very large part within the uncertainty ranges of these estimates. In other words, there does not seem to be any significant change in each Party’s estimated emissions between the six different submissions analyzed in this study. This is even more the case when the emissions and removals from Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) are excluded from the analysis. The changes in the estimate for this sector are in many cases very large, signaling that probably the IPCC methods for this sector is either not well developed yet or not well understood or similarly interpreted by the experts both in the countries and in the inventory teams. The impact on the value of the national totals however is relatively limited.

Based on this result we propose a simpler and cheaper approach for the review, where review teams decide to not pay much attention to smaller issues that might be present in the submission, provided that the submission in general is prepared taking the Convention’s transparency, consistency, comparability, completeness and accuracy criteria into account. Such a simplification might be necessary for the international community to be able to continue to ensure sufficient quality of nationally reported data when implementing and monitoring the decisions and provisions of the recent Paris Agreement.

[This discussion paper has been submitted to the Carbon Management journal.]

Background

The UNFCCC and KP reporting obligations

In early 2016, the Kyoto Protocol (KP) under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was finalized by the review of the so-called true up process[1]. This process enabled Parties to the KP to solve any remaining issues related to meeting the targets set in the protocol. A recent paper by Shishlov et al. [1] concluded that all Parties, with the exception of Ukraine, indeed did meet their commitments, in some cases by using the flexible mechanisms (e.g., Clean Development Mechanism emission offset credits) as defined under the KP. Shishlov et al. used the final annual submissions by all Parties to the protocol.

Data to be used when assessing compliance with agreements under the UNFCCC must be derived from the annual inventory submissions. The Parties to UNFCCC have set up an elaborate system of review by independent expert teams ensuring that Parties have reported their inventories according to the agreed upon procedures and methods. Through this process all Parties can be confident that the reported data are fit for use for application under the Convention [2]. The annual reporting is a cyclic process, allowing Parties to update and improve data in subsequent submissions, including in response to issues identified in previous reviews and as a consequence of improvement programs developed by the countries themselves.

This reporting and review system for developed country Parties (Annex I) has been operating since the early 2000s.[2] National inventories have been submitted and reviewed many times and the expectation is that this has greatly improved the quality of the inventories. This paper assesses whether the inventories improved through this cyclic process by analyzing the annual inventory submissions of all Annex I Parties. In addition, this article provides a general overview of the level of effort made by both the UNFCCC secretariat and the experts performing the reviews to administer the process.

The UNFCCC Reporting and Review Process

The UNFCCC has decided that Parties to the Convention must submit on a regular basis national reports on implementation of the Convention to the Conference of the Parties (COP) [3]. The required contents of these national reports and the timetable for their submission are different for Annex I and non-Annex I (developing country) Parties. One of these reports concerns the submission of greenhouse gas (GHG) emission inventories by Annex I Parties. Each national report submitted by an Annex I Party is subject to an “in-depth” review conducted by an international team of experts and coordinated by the UNFCCC secretariat. Reports for non-Annex I Parties undergo an international verification process through an international consultation and analysis.

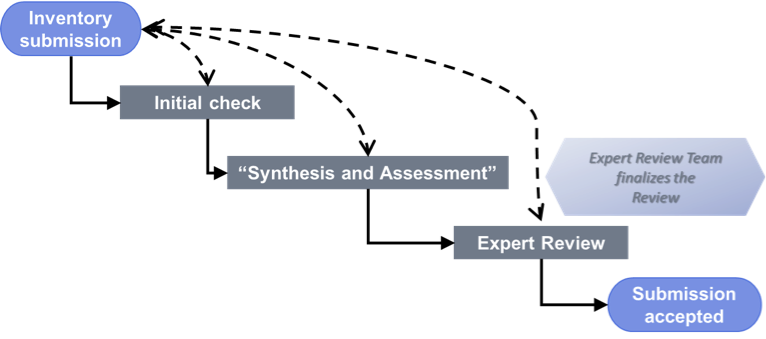

The UNFCCC reporting and review process for annual inventory submissions [3] is an annual, cyclic process (Figure 1) where each Party is required to submit a national emissions inventories for all years between the base year (1990) and the year N, before April 15th of year N+2. This gives the Party 15 months’ time to prepare the inventory submissions. Each submission consists of a number of predefined data tables (Common Reporting format, CRF) and a so-called National Inventory Report (NIR). Finally the data reported by the Party and, if necessary updated as a result of issues identified during the review, enter the UNFCCC accounting and review database[4] to be used for the final assessment on whether or not a Party has met its quantitative obligations.

After the submissions due date, the UNFCCC starts its annual review process in three successive steps: the initial check, the synthesis and assessment and the expert review (Figure 1; see also [4] for a brief summary), that in practice could run a few months into year N+3. So all national submissions are reviewed and accepted for use in the processes of the UNFCCC and its Kyoto Protocol within little more than two years after each inventory year.

- Figure 1 Top: Over-all time schedule of the UNFCCC reporting and review process. This timeline is repeated each year: emissions in year N are reported by mid-April year N+2 and subsequently reviewed; Bottom: overview of the review process

The purpose of these national reports is to inform all Parties of the progress made by each individual Party in complying with the decisions of COP and the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol (CMP). The expert reviews assess these reports against all required procedural and methodological requirements laid down in the UNFCCC reporting requirements and the relevant guidance of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)[5]. It should be stressed that the quality criteria for these reports differ from those of a scientific analysis. The review validates the submissions against agreed upon requirements and does not verify against other independent measurement methods as described by Swart et al [6].

Expert Review Teams (ERTs) consist of six different roles: a generalist and five sector experts (Energy; Industrial Processes and Product Use (IPPU); Agriculture; Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF); Waste). In practice two types of expert reviews are used: in country reviews and centralized reviews. The third option, desk reviews, are very seldom used.

In country reviews are performed for one Party at the time with one expert in each role. Two of these experts also act as Lead Reviewers, managing the team and coordinating the interaction with the Party and the UNFCCC secretariat. Centralized reviews review three to five Parties at the same time at the UNFCCC premises in Bonn and consist generally of two experts in each role. Again two of the ERT members act as Lead Reviewer. Each ERT is supported by a UNFCCC staff member as review officer.

The ERTs not only review the numerical information in each Party’s annual inventory submission, but also assess the way the Party ensures that it can provide all information in a transparent, consistent, complete, comparable and accurate (TCCCA) manner. To this end each Party must have in place a so-called National System that performs all functions and tasks required by the COP and CMP decisions, including the establishment of all institutional arrangements that are needed to ensure a smooth and steady dataflow towards the emission inventory. This reporting and review work requires a significant effort by the Party, the Expert Review Teams and the UNFCCC Secretariat.

Inventory Quality and Uncertainties

As discussed elsewhere, the understanding of inventory quality depends on the purpose for with the inventory is compiled. Where emission data are reported under community-right-to-know legislation these data are published as soon as these are reported, whereas national inventories are generally carefully compiled, using sophisticated quality control and quality assurance procedures before the data are published on a more or less aggregated level [7]. Swart et al [6] discuss the differences in scientific quality of emission inventories and the quality as defined by the UNFCCC reporting and review process. These authors argue that, although the scientific quality could be challenged, the quality in terms of the requirements of the UNFCCC and KP might very well be sufficiently met. Contrariwise, any scientific use of officially reported national greenhouse gas inventories should be considered with care as these might not necessarily reflect the most recent and best science that became available after the respective guidelines have been established and agreed upon.

Related to inventory quality is also the concept of uncertainties [8]–[12]. Although Parties are required to report the uncertainties in their annual submission, these uncertainties are of no relevance for the assessment whether or not the quantified emission reduction targets have been met. These are either met or not met. Uncertainties in national total emissions are generally in the range between 3 and 8 per cent [3].

This study

This study includes a web based survey on the level of effort put into the UNFCCC review process by ERTs and the UNFCCC secretariat. It further analyzed the subsequent inventory submissions from all Annex I Parties at a relatively high level of aggregation to assess how much the reported emissions for the year 2008 have been changed in the submissions. Finally, we assessed these changes against the effort put into the process and provide recommendations for the further development of the UNFCCC review process.

Method and data

Web based survey

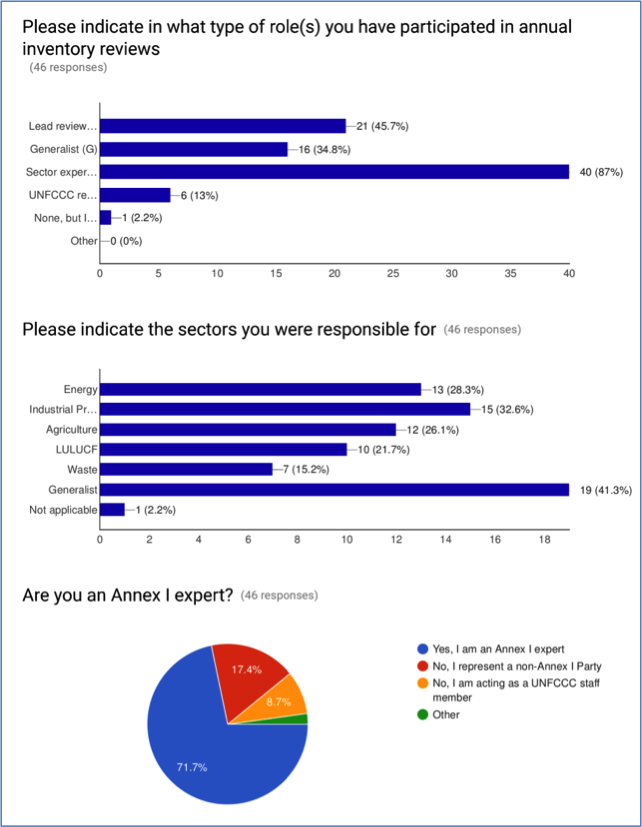

A few weeks prior to the thirteenth UNFCCC Lead Reviewers meeting (February 27th to March 2nd 2016[5]) about 200 individuals involved in the process either as (lead) reviewer or as UNFCCC staff, were invited by e-mail to complete a short questionnaire[6] on the effort individuals have inputted into the review process in the various roles. Within two weeks, we received responses from 46 respondents. Most of these experts participated in the process in more than one role and answered the questions on the effort needed for each role. Figure 2 provides an overview.

All respondents, except one, participated in the review process as sector expert. About half of them were served as a lead reviewer at least once and 19 experts have acted as generalist. Figure 2 also shows that the experts were relatively well distributed across sectors. About 70 per cent of the respondents were from Annex I Parties and a bit less than 20 percent representing non-Annex I Parties. Finally, six respondents have acted as UNFCCC review officer, supporting the review teams.

- Figure 2 Response to the questionnaire on efforts put into the UNFCCC review process. The response rate is about 20%

Greenhouse gas emission inventory data

National GHG emissions from [12] are extracted from databases made available to the ERTs (Locator database) for the reviews of the submissions of 2007 and 2010 until 2014, covering all KP years. They are aggregated to the 12 main sectors as indicated in Table 1. The 2007 database is chosen for use in this study because the 2006 and 2007 submissions were used to set the targets for the KP. The National Systems in most countries were well established by this time to make submissions of the initial reports under the KP, as is reflected in the reports of the annual Lead Reviewers meetings[7]. The review process was still developing during earlier years, so the use of data in inventories submitted before 2007 is problematic.

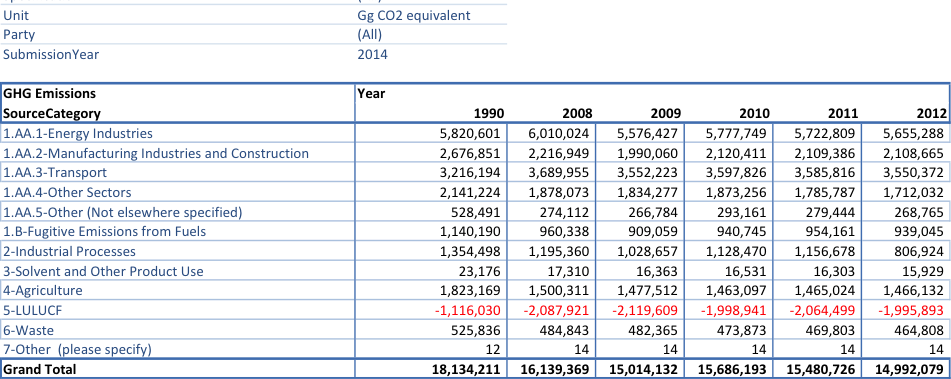

Table 1 below provides an overview of 2014 submissions from Annex I Parties. Data from individual EU Member States were used separately throughout this study. USA, Canada, Turkey and Ukraine are included, unless otherwise indicated. The data will be available as additional material to this paper.

Submitted data might have been changed and resubmitted during the review process. Such updated estimates are included in the next year’s submission of each Party. This study uses the data as they were originally submitted at the start of each subsequent inventory cycle.

- Table 1 Total GHG emissions by main sector as reported by Annex I Parties in their 2010 annual submissions to UNFCCC

Results

Meeting the Kyoto Protocol target

Figure 3 presents the time series of the sum of all national totals, except Ukraine, for each year between 1990 and 2012. About one third (1990) to two fifth (2012) of the emissions reported in the annual inventory submissions occur in Parties who did not participate in the Kyoto Protocol reduction targets (US, Canada, Turkey).

- Figure 3 Time series of total GHG emissions in the annex I Parties, 2014 submission data; for country groupings see the Appendix

Figure 3 shows that the total reported GHG emissions in the Kyoto Protocol commitment period (2008 – 2012) decreased 11 to 17 % below the 1990 value. The overall objective of the Kyoto Protocol therefore seems to be met, as was also concluded by Shishlov et al [1], despite the fact that a few Parties did not participate in the KP quantified reduction targets (United States, Canada, Turkey). It is also shown that this result was due in large part to the economic changes in the former Soviet Union countries and the Central European EU Member States.

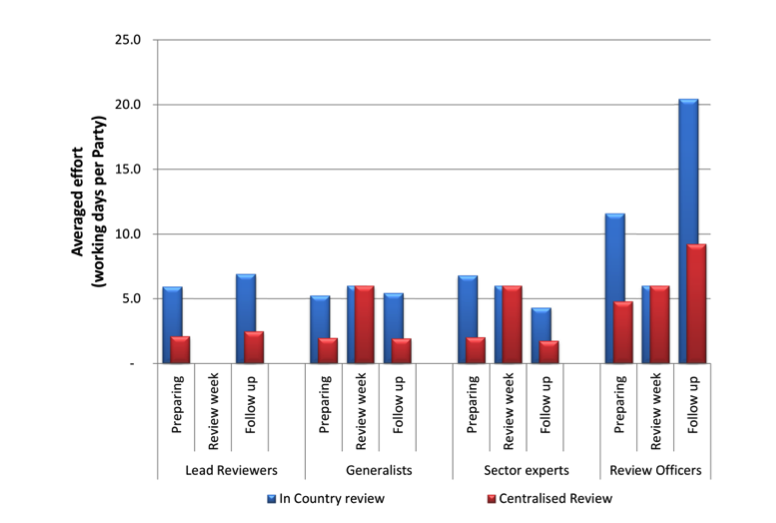

The effort invested in the review process

The estimated effort invested into the review process by the ERTs and the UNFCCC secretariat is summarized in Figure 4. The expert review takes place in three phases: preparation, the review week, where the ERT works together either at the premises of the Party (in country review) or at the UNFCCC offices in Bonn (centralized review) and the follow-up of the review after the review week, when the report is finalized and comments from the Party are invited and dealt with. The review week results in a zero order review report that provides a complete overview of issues identified in each Party’s submission. All issues identified by the ERT are communicated to the Party, who is allowed to formally respond. After the review week, the ERT assesses additional information and answers provided by the Party and prepares a final draft of the review report, which is then sent to the Party for comments. Finally, the ERT considers any responses or comments from the Party on the draft report and produces a final report.

Preparing for the review week includes several tasks:

- Thoroughly reading through the Party’s national inventory report;

- Performing the early stages: initial check, synthesis and assessment and the communication with the Party; [4]

- Figure 4 Estimated work load for in country reviews and centralized reviews by role and review phase (top) and total for each review.

- Assessing the issues identified by the UNFCCC secretariat in the Synthesis and assessment report and the Party’s response to these issues; and

- Drafting some preliminary questions to the Party on whatever the expert finds in these documents.

The ERT members responding to the questionnaire estimated the work load for preparing a centralized review as two working days per Party for each sector expert and generalist and an additional two days for the lead reviewer. For in country reviews the estimate was six to seven working days.

The effort required for UNFCCC review officers is significantly higher. A review officer needs almost five working days per Party for a centralized review and twelve working days for an in country review. Note that centralized reviews address three to five Parties. So, the preparation of a centralized review will require a similar or even a higher effort than an in country review for each team member. Since centralized reviews generally include two experts for each role and sector, this workload is shared by more individuals.

During the review week, all ERT members and the UNFCCC review officers work for six full days (Monday morning until Saturday end of afternoon) closely together and in frequent contact with the Party’s experts. Because there is essentially no time to do anything else during this week, the effort during the review week is for all participants set to six full working days. Note that the lead reviewer also has a role as a sector expert or generalist, and therefore, the workload for lead reviewers during the review week is set to zero in Figure 4, to avoid double counting.

The effort required from staff at the UNFCCC secretariat to finalize review reports is about double the effort needed for preparation. Strict and intensive quality assurance and quality control procedures are applied to ensure that all reviews are comparable, consistent and fair across all Parties.

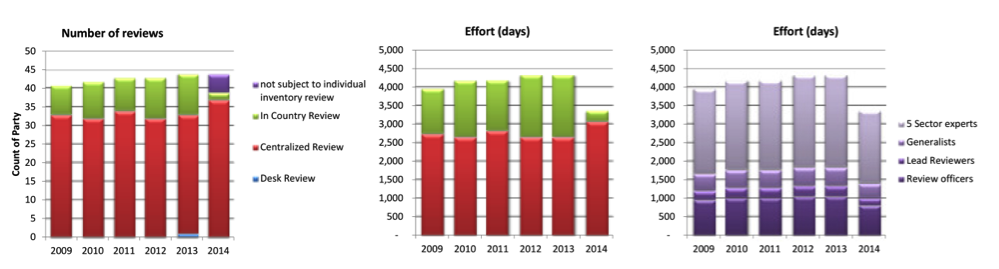

Aggregating the work load for one Party over all members of an ERT and UNFCCC secretariat staff (Figure 4, bottom), shows that the average workload for reviewing one Party is roughly 150 working days for an in country review and 83 working day for a centralized review. The number of reviews increased from 2009 to 2014 from 40 to 44 (Figure 5), with about 20% of the reviews being in country and, apart from 2014, the rest centralized. In 2014, a number of Parties were not subjected to an individual review and one Party was reviewed in a desk review, where experts work from their own desks at home.

- Figure 5 Total effort invested annually in the UNFCCC review process by ERTs and UNFCCC staff

Using the data from Figure 4, Figure 5 presents the combined total annual work load for both the ERTs and secretariat staff. This total work load amounts to about 4000 working days per year for an annual review cycle covering around 40 Parties (i.e., only Annex I). About one quarter of this is needed for the tasks to be performed by UNFCCC review officers.

Inventory improvements

Parties often recalculate their GHG emissions estimates for select sources or uptakes in specific sinks in response to preview review reports. Recalculations can also occur due to updated activity data or new information on emission factors. This study assumes that these recalculations are largely improvements in response to the review processes, both within the country itself and by the independent reviews under the UNFCCC. Analyzing these changes would therefore reflect possible improvements made in the inventory submissions over time.

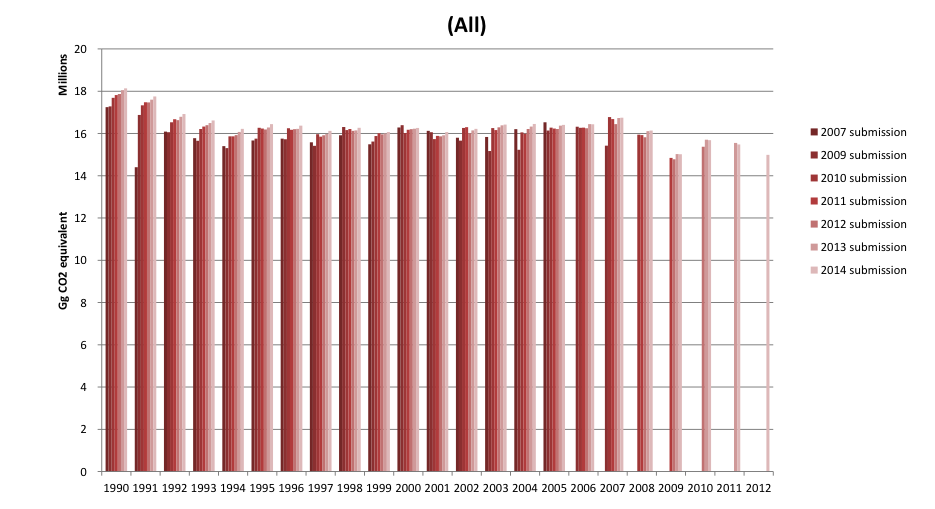

- Figure 6 Total annual GHG emissions in all Annex I Parties as reported in the annual submissions of 2007, 2009, 2010 to 2012.

Since estimates for emissions and removals in the LULUCF sector show much higher year to year changes across annual submissions than for all other sectors, we will look at the GHG emissions for all other sources (the so-called KP Annex A sources) first.

KP Annex A sources

Figure 6 shows the subsequent estimates for the total annual GHG emissions in all Annex I Parties, except Ukraine, as derived from the national GHG inventory submissions in the years 2007 (inventories for 1990 – 2005), 2009 (1990 – 2007 inventories) and 2010 to 2014, including successively the Kyoto Protocol year 2008 to 2012. Obviously, the 2014 submission is the only one including emissions for the year 2012 etc. Although in the later years of the time series no clear trend in the estimates for each years seem to be visible, the estimates for the earlier years, including the base year 1990, seem to increase over time in the subsequent submissions. This is at least partly due to the fact that some Parties (Turkey, Kazakhstan, Malta, Cyprus) started to participate in the reporting after 2007.

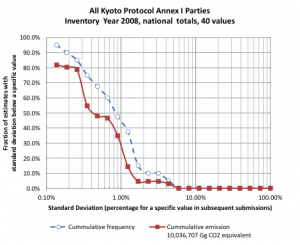

Figure 7 (left) presents an analysis of these data for the inventory year 2008, for which five successive estimates are available. Here the standard deviation for all available estimates for the national total emissions, excluding LULCF, for 2008 in each reporting Party is calculated. The graph presents the cumulative frequency of the number of national totals and the value of the totals as a function of the value of the standard deviation as percentage of the national total. The latter is interpreted as a measure of the variance of this estimate over different submissions. We observe the following:

- No more than 30 to 40 % of these estimates vary more than plus or minus a few percent (90 percent of the values are within twice the standard deviation, assuming a normal distribution). This reflects quantitatively the year to year changes in the inventory submissions.

|

|

Figure 7 Percentage of submissions (open circles) and reported emissions (squares ) where the standard deviations of reported emissions for each Party for each year is above the value on the horizontal axis as an estimate of the variance of the reported national totals (left) and of the ten major sectors (right); excluding LULUCF

- Where there are somewhat higher values for the standard deviations between successive submissions, they seem to occur in a few inventories with lower national greenhouse gas emission totals.

Figure 7 (right) presents a bit more detailed overview. Rather than the national totals, the totals in each main sector (see Table 1) except LULUCF and “other” are analyzed here. We see that the standard deviations now are two to three times higher, consistent with the observation that we have ten times as many vales in the analysis. Aggregating ten random variations at the main sector level to one national total would lead to a standard deviation that is a square root of ten smaller. Furthermore, some of the changes might be due to re-allocations of specific sources, leading to an increased estimate for one sector and a decreased estimate for another.

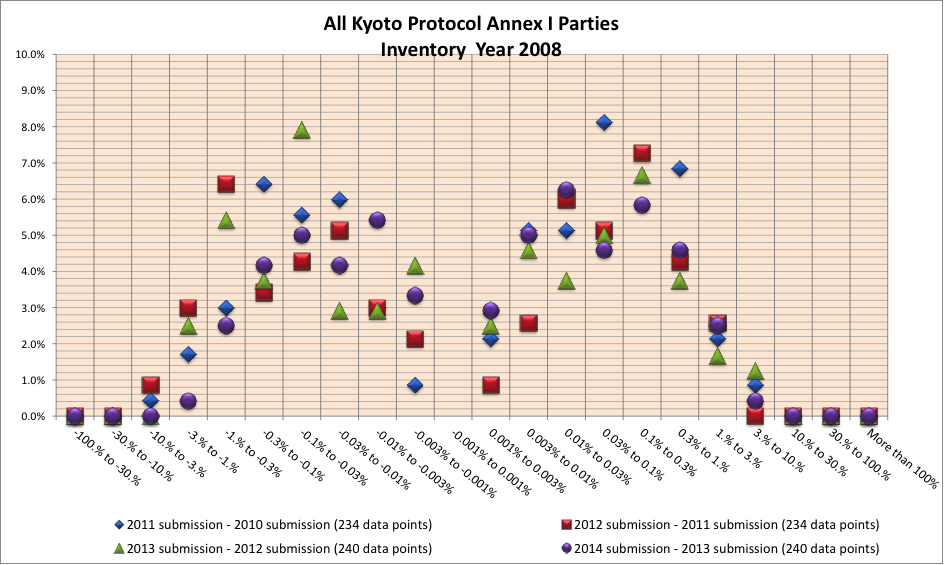

These changes seem to be in the same order of magnitude or even smaller than the uncertainty ranges reported by the Parties in their annual submissions, both for national total emissions and for the totals for each major sector.

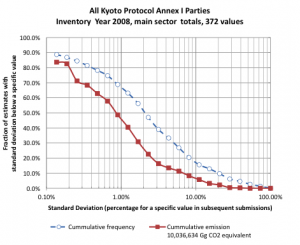

In Figure 8 the changes in the 2008 emission estimates for each pair of two successive submissions are shown. Note that the horizontal axis is a mirrored logarithmically defined set of concrete value bins. The left part of the graph shows large to small decreases, whereas the right part shows small to large increases. There appears not to be any clear structure in these scatter plots, apart from the fact that the majority of changes are between plus or minus 0.03 and 3 per cent. There seem to be as many decreases as there are increases.

- Figure 8 Distribution of the relative changes in the subsequent submissions in 2010 until and including 2014 at the level of the sectors listed in Table 1, excluding LULUCF

This observation suggests that there is no evidence that the changes in estimates for a given reported variable between successive GHG reports are anything other than random and can be attributed primarily to the uncertainties in the changing data and methods. Whenever an improved or changed method is applied, this leads to indeed a change in the estimate, but the new estimate almost always remains within the uncertainty range of the older one. In other words, we cannot conclude from the data submitted by the Parties that later estimates are indeed significantly different from the earlier ones.

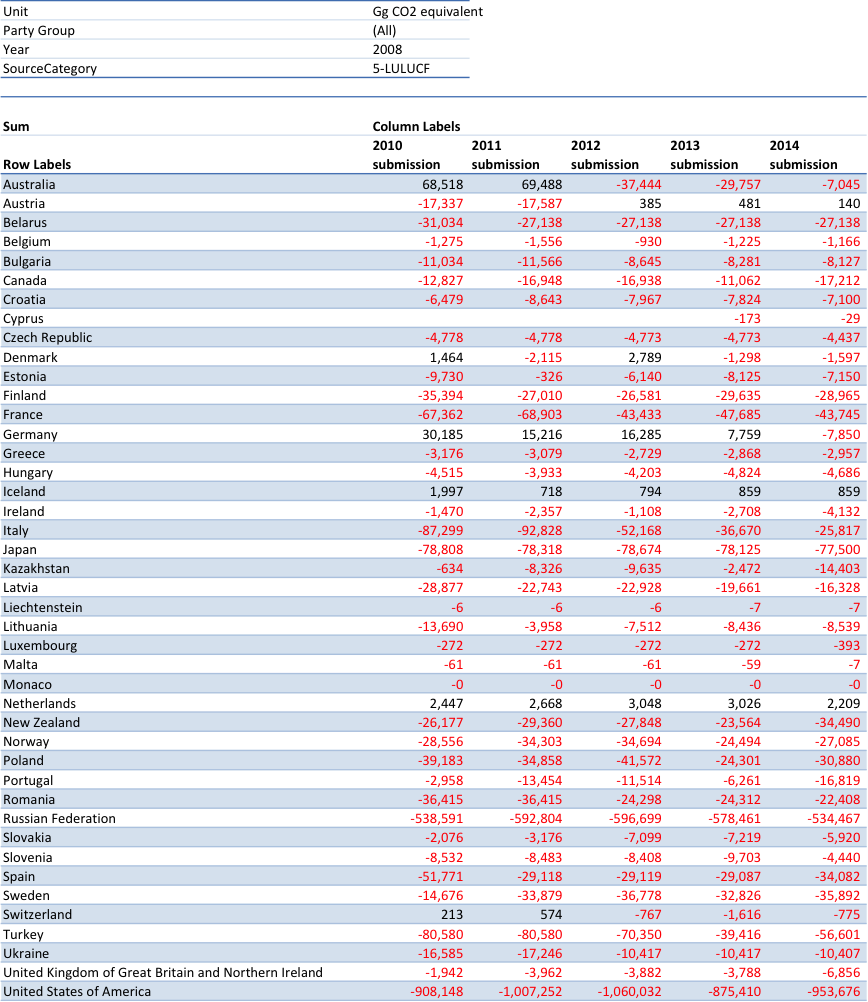

LULUCF

As already indicated above, the reported values for the emissions and removals within the LULUCF sector vary considerably more than those in other sectors (Table 2). For some Parties (Australia, Austria, Denmark, Germany and Switzerland), some submissions reported emissions for this sector and other submissions report removals. This makes further analyses in this study quite impossible. The large variations for the reported emissions and removals in this sector might indicate that the technical guidance, provided by IPCC [5] is either not well interpreted and applied by many Parties and the respective ERTs or not sufficiently developed yet.

- Table 2 2008 LULUCF emissions and removals as reported by Annex I Parties with their annual submissions of 2010 to and including 2014.

Discussion and Recommendations

The analyses in this study have shown that on the one hand both the ERTs and the UNFCCC secretariat invest a significant amount of work into the review of the annual greenhouse gas emission inventory submissions by Annex I Parties to the UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol. This work provides confidence for the COP that the data submitted by Parties are fit for use under the processes of the UNFCCC and the KP. As is explained by Swart et al [6], this is a different process than a scientific assessment.

The workload for this process amounts to about 4000 working days per year, about one quarter of which is required for the UNFCCC secretariat. Despite this significant amount of effort, statistical analysis did not identify significant change in the reported national total emission estimate nor in the main source category totals for each reporting Party over the course of reporting the KP commitment period. The changes in subsequent submissions were all within the uncertainty range of these estimates and did not show a clear trend. They are what one would expect from different estimates for the same real value using different input data and/or methods: random variations within the uncertainty range itself. Even in the case that all of the changes are due to issues raised by the subsequent ERTs, including the so-called “adjustments” [2], these did not significantly change the numbers. This makes these changes technically irrelevant as they cannot be proven to be closer to the real world value than the earlier estimate.

Of course, there might be a problem when the reported emissions are very close to the target and a compliance check needs to be performed. Whether or not a Party complies with a quantitative target can, under the UNFCCC or the KP, only be answered with a “yes” or a “no”. So when the reported emissions are such that the quantitative target is within the uncertainty range of the inventory, the random error, linked to the uncertainty in the reported emissions, might in fact randomly lead to a “yes” in some cases and a “no” in others. Furthermore no ERT could ever conclude whether it is a “yes” or a “no” based on technical or scientific reasons. Whatever the ERT would conclude: there will be scientific uncertainty on the outcome of the process. Fortunately, this possibility so far has not occurred.

A related issue the difference between the target and the reported emissions in terms of market value. The uncertainty in the inventory estimate is, at a given market price for tradable emission units, directly converted into an uncertainty in the amount of money needed to buy or the amount of money received when selling emission allowances or credits. This problem cannot be solved by scientific reasoning or analysis.

The review process, therefore, has some aspects of using a sledgehammer to crack a nut: it needs a large amount of resources but does not appear to result in a significant quantitative improvement of the inventories. This does not necessarily mean that all effort put into the review process is wasted: there will be still a qualitative improvement, enhancement of confidence, and deterrence of cheating. The task of the ERTs is then essentially to provide confidence in the data reported by each Party to the UNFCCC and the KP that the inventories submitted are good enough to be used under the processes of these international agreements. The reviews have increased the quality of the inventories in terms of transparency, consistency, completeness, comparability and accuracy[8], the so-called TCCCA quality criteria as defined by the UNFCCC reporting and review guidelines [2], [7]. This is reflected in the growing size of the NIRs accompanying the successive submissions.

The situation is different in the LULUCF sector. Very large year-to-year estimates for the same sector in the same country occur between successive submissions. Since these large variations have repeatedly been accepted by consecutive ERTs in their annual reviews, the problem here might more likely be in the (interpretation of the) IPCC Guidance than in the UNFCCC review process. Successive estimates for the same source category for the same year change dramatically from year to year. Apparently the IPCC Guidance for LULUCF is, despite the size of the LULUCF volume in the 2006 Guidelines[5], either not sufficiently developed or still being interpreted differently by different experts, both at national teams and by ERT LULUCF experts. In both cases this would call for further clarifications on what data are needed and what methods will provide an estimate where Parties could have confidence that these are good enough for application in the policy processes of the UNFCCC and the KP. The analysis shows that this is not the case for inventories submitted for the first commitment period of the KP.

To decrease the burden put on the ERTs, the UNFCCC secretariat and on the Parties’ national systems and experts, ERTs could decide to treat as immaterial any issue that would change the national total or totals in the main sectors by less than half or one third of the respective uncertainty range. Any such issue would, even when the ERT was correct regarding the issue, not change the confidence Parties have in the quantitative applicability of this specific inventory for the processes under the UNFCCC or its protocols. This approach could be appropriate if the reporting Party’s National System has been reviewed and no issues were detected that would hamper the functionality of their National System in delivering all requirements in UNFCCC and KP decisions and no changes in their National System are reported.

For LULUCF, better understanding of the IPCC Guidance or more objective procedures would be needed. Without this change, one wonders whether reviewing the LULUCF sector makes any sense from the technical or scientific point of view. LULUCF sector reviews require a lot of resources and produce a highly ambiguous result on whether or not the Parties can be confident that the data for LULUCF are good enough for the processes under the Convention or its protocols. If it is not this apparent ambiguity but real scientific uncertainty, that causes the large changes in subsequent submissions in this sector, it would probably be wise to exclude LULUCF from reporting altogether.

Following the Paris Agreement [14] and its inclusion of approximately 190 countries, many more than 40 Parties will need to report their inventories and have those some way or another be reviewed. One now wonders whether the international community will be able to afford the resources for 150 (for in country reviews) or 80 (for centralized reviews) working days for each submission by a Party. Even if the frequency of reviews is agree to be once every two years rather than annually, the quadrupling in the number of inventories would lead to doubling off the workload of both the UNFCCC secretariat and the ERTs. There is no reason to believe that the “international verification process through an international consultation and analysis”3 would require significantly less effort.

Given the observation that the UNFCCC is always short of independent experts and staff for the review processes, it becomes even more evident that the review process needs to be made less resource demanding. ERTs could decide to behave a bit more as experts who consider uncertainty and who are given more discretion to determine whether or not the data are good enough for the processes under the UNFCCC. As technical experts, they should understand that any change within the uncertainty range is not a significant improvement of the scientific accuracy of the inventory. This would mean that any issue that changes the national total emissions less than, for example, half or one third of the uncertainty range for the full inventory, would not change the national total significantly and probably is not worth looking at it, provided that:

- the source of the activity data is mentioned in the NIR (transparency);

- the first automated stages of the review process (the so-called synthesis and assessment, [7]) did not identify any serious issue (time series consistency and comparability); and

- the implied emission factors are within the uncertainty range of the IPCC tier 1 defaults (comparability and accuracy [5]).

By including these considerations in a relatively simple, automated check list, the work of the ERTs, the UNFCCC staff and the national experts could be greatly facilitated. As discussed by Swart et al [6], this streamlined approach may slightly decrease the scientific quality of the submitted inventories, but they would likely still be of sufficient quality for policy oriented use under the UNFCCC. This approach should work for all sectors, with the probable exception of LULUCF, where the guidance is apparently insufficiently developed.

Specific decisions of either the COP or the CMP are probably not needed to change the working style of the ERTs to implement the recommendations above. The ERTs consist of experts who should know and understand the consequences of the fact that the inventory and all the underlying data are subject to uncertainties. This expertise would be sufficient to convince the COP or CMP, for example through discussions with the KP Compliance Committee, that any issue that would change the national total less than the uncertainty range therein, is not worthwhile looking into, provided that the TCCCA quality criteria are met.

As discussed above, there is only one minor problem here: whether or not a Party complies with the decisions of the UNFCCC and its protocols can only be answered with a “yes” or a “no”. In cases where the distance between the target and the estimate of the inventory is smaller than the uncertainty range, issues that are scientifically irrelevant, might become relevant in procedural sense. However this situation is not very probable and did not occur during the first commitment period under the KP.

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank the UNFCCC secretariat for allowing me to use the so-called Locator databases, annual extracts from the UNFCCC inventory database provided to the ERTs for use during their analyses. The data on the UNFCCC website [12] do only provide the latest submitted data.

The estimate of work load was based on a quick web based survey under the Lead Reviewers and UNFCCC staff, prior to the thirteenth Lead Reviewers Meeting[9] early 2016. I thank many of my colleagues Lead Reviewers for commenting on my presentation of the preliminary results at this meeting.

Endnotes

[1] http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/true-up_process/items/9023.php

[2] The Annex I Parties are: Australia, Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, European Union, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Monaco, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russian Federation, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States; not all of these Parties however have quantified emissions reduction targets under the Kyoto Protocol.

[3] http://unfccc.int/national_reports/items/1408.php

[4] http://unfccc.int/ghg_data/kp_data_unfccc/compilation_and_accounting_reports/items/4358.php

[5] http://unfccc.int/files/national_reports/annex_i_ghg_inventories/review_process/application/pdf/draft_conclusions_lrs_13th_v01_4march2016_incl_location_asr.pdf

[6] The questionnaire is available as an additional document tot his paper

[7] http://unfccc.int/national_reports/annex_i_ghg_inventories/review_process/items/2762.php

[8] Please note that the definition of Accuracy under UNFCCC includes the phrase “as far as can be judged”, explicitly disconnecting it from a scientific definition of “accuracy” where the link to the real world value is used.

[9] http://unfccc.int/national_reports/annex_i_ghg_inventories/review_process/items/2762.php

References

[1] I. Shishlov, R. Morel, and V. Bellassen, “Compliance of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol in the first commitment period,” Clim. Policy, pp. 1–15, 2016.

[2] UNFCCC secretariat, “Reporting and Review for Annex I Parties under the Convention and the Kyoto Protocol.” [Online]. Available: http://unfccc.int/national_reports/reporting_and_review_for_annex_i_parties/items/5689.php. [Accessed: 06-Feb-2016].

[3] UNFCCC secretariat, “Annex I Greenhouse Gas Inventories.” [Online]. Available: http://unfccc.int/national_reports/annex_i_ghg_inventories/items/2715.php. [Accessed: 05-Feb-2016].

[4] T. Pulles, “The Kyoto Protocol reporting and review process,” Greenh. Gas Meas. Manag., vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1–4, 2012.

[5] IPCC, “2006 IPCC Guidelines,” in 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, Prepared by the National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme, 2006.

[6] R. Swart, P. Bergamaschi, T. Pulles, and F. Raes, “Are national greenhouse gas emissions reports scientifically valid?,” Clim. Policy, vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 535–538, 2007.

[7] T. Pulles, “Quality of emission data: Community right to know and national reporting,” Environ. Sci., vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 151–160, Sep. 2008.

[8] K. Rypdal and W. Winiwarter, “Uncertainties in greenhouse gas emission inventories — evaluation, comparability and implications,” Environ. Sci. Policy, vol. 4, no. 2–3, pp. 107–116, Apr. 2001.

[9] P. Fauser, P. B. Sørensen, M. Nielsen, M. Winther, M. S. Plejdrup, L. Hoffmann, S. Gyldenkærne, M. H. Mikkelsen, R. Albrektsen, E. Lyck, M. Thomsen, K. Hjelgaard, and O.-K. Nielsen, “Monte Carlo (Tier 2) uncertainty analysis of Danish Greenhouse gas emission inventory,” Greenh. Gas Meas. Manag., vol. 1, no. 3–4, pp. 145–160, 2011.

[10] W. Winiwarter, “National Greenhouse Gas Inventories: Understanding Uncertainties versus Potential for Improving Reliability,” Water, Air, Soil Pollut. Focus, vol. 7, no. 4–5, pp. 443–450, Jun. 2007.

[11] A. Ramírez, C. de Keizer, J. P. Van der Sluijs, J. Olivier, and L. Brandes, “Monte Carlo analysis of uncertainties in the Netherlands greenhouse gas emission inventory for 1990–2004,” Atmos. Environ., vol. 42, no. 35, pp. 8263–8272, 2008.

[12] Annex I UNFCCC Parties, “National Inventory Submissions.” [Online]. Available: http://unfccc.int/national_reports/annex_i_ghg_inventories/national_inventories_submissions/items/8812.php. [Accessed: 05-Feb-2016].

[13] Gillenwater, M., Sussman, F. & Cohen, J. Practical Policy Applications of Uncertainty Analysis for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. Focus 7, 451–474 (2007).

[14] UNFCCC, “Report of the Conference of the Parties on its twenty-first session, held in Paris from 30 November to 13 December 2015 Addendum Contents Part two: Action taken by the Conference of the Parties at its twenty-first session,” Decision 1/CP.21 Adoption of the Paris Agreement, 2015. [Online]. Available: http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/10a01.pdf. [Accessed: 03-May-2016].

Leave a Reply