The Next Carbon Accounting Frontier

We are on the next carbon accounting frontier: policy-level GHG accounting for the Paris Agreement.

The GHG Management Institute (GHGMI) is building global capacity to implement the Paris Agreement, and we believe professional carbon measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) is core to this mission. In furtherance of GHGMI’s mission, I am leading a team developing greenhouse gas (GHG) impact assessment guidance for agriculture and forest policies and actions under the Initiative for Climate Action Transparency (ICAT). This new kind of policy-level GHG accounting framework can be viewed as an amalgamation of existing GHG inventory and project-level accounting frameworks, as well as theories of policy impact assessment.

I am particularly optimistic and excited about the central features of the agriculture and forest guidance – policy descriptions, causal chains, and policy implementation analysis – that will support the transparent and credible tracking of policies to achieve Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). This post will explain the key advances in these two sector-specific guidance documents that are crucial contributions to a new policy-level GHG accounting framework, and ask you to participate in the ICAT guidance public consultation (open through September 25th).

The Problem and Why We Need Guidance

NDCs are pledges for mitigating GHG emissions that are voluntarily laid out by each Party (country) to the Agreement. We all hope these pledges will result in real mitigation and effectively contribute to a long-term global effort of keeping global warming from exceeding 2°C. Clearly, a lot is riding on these NDC pledges. Imagine if you had a life-threatening blood pressure problem requiring daily management of diet and stress, but you didn’t have a way to monitor your blood pressure. In many ways, this is the situation we are in right now with NDCs. We have a dangerous global problem, an accord for managing it, but an insufficient system, yet, for monitoring progress and compliance. We’ve written previously on the serious complexity of what will be required of post-Paris MRV. As GHG MRV specialists, we know the job of transparently, credibly, and readily tracking NDCs will fall to us.

But first, what does it mean for NDCs to be ambitious and effective?

I think the way we know that NDCs are ambitious is through assessing how much the policies and actions pledged within them will impact GHG emissions. Separately, the way we know they are effective is to credibly demonstrate that these same policies and actions are the cause of those GHG impacts. Which means, we need a way to attribute GHG impacts to policies and actions, and demonstrate with evidence a causal link between the two.

How, exactly, do we do this? We have a lot of tools for carbon accounting that are relevant, but none on it’s own is sufficient.

National GHG inventories alone are not sufficient.

National GHG inventories have long been a requirement of Parties to the UNFCCC, and will remain a core reporting mechanism under the Paris Agreement. National GHG inventories can track progress on economy-wide absolute emission reduction targets. They are essential for measuring the overall impact each country has on global GHG concentrations. But national GHG inventories are insufficient for tracking progress on many NDCs, especially where data are needed to attribute GHG emission trends to specific policies and actions.

Project accounting is helpful, but also not sufficient.

Project-based accounting provides methods for meticulously ascribing causation – confidence that the GHG impact that is measured occurred as a result of an intervention. This is done using highly specific project definitions, additionality tests, transparent assessment of business as usual (or baseline) scenarios, clearly and thoroughly defined GHG accounting boundaries that ensure impacts on all relevant GHG sources and sinks are quantified, accurate GHG quantification of GHG emission and removals, and specific project monitoring requirements. But projects typically occur at a smaller scale and under more controlled or specific circumstances than the broader type of policies and actions pledged by NDCs. As a result, project-based accounting protocols are not suitable for evaluating most NDC pledges.

We need a new paradigm for policy-level GHG accounting.

We need to borrow from and adapt GHG inventory and project-level accounting into a new policy-level GHG accounting framework that enables consistent, credible, and transparent tracking of the effectiveness and ambition of policies within NDC pledges.

ICAT: A start on the solution

In response to this long-standing problem, ICAT was launched in 2016 to provide tools and support that can be used to report on Paris Agreement commitments. The new ICAT series consists of “impact assessment guidance” for evaluating how policies and actions impact GHGs, sustainable development and transformational change, as well as “supporting guidance” covering stakeholder engagement, technical review, and non-state and subnational action.

My team at GHGMI has been drafting sector-specific guidance for the agriculture and forest sectors based on the general Policy and Action Standard (P&AS). The collaboration is wide. Carolyn Ching at Verified Carbon Standard is directing the effort and two sector-specific technical working groups provided input and drafting. Together, this work on agriculture and forests is a solid start at developing a policy-level accounting framework for tracking ambition and effectiveness of NDCs.

Three ways the ICAT guidance will help with tracking ambition and effectiveness of NDCs

- Standards for Policy Descriptions

To attribute GHG impacts to specific policies and actions, you first have to clearly specify the policy and/or action being implemented and how it is predicted to induce GHG impacts. However, our review of NDCs and NAMAs revealed a tendency to commit to implementing mitigation practices or new technologies without articulating a corresponding policy instrument to drive implementation.

Therefore, in the ICAT guidance we describe several common types of policy instruments and examples in the agriculture and forest sectors, and separately, elaborated common types of mitigation practices and technology changes for reducing GHG emissions and enhancing removals. We recommend that policy descriptions include both a policy instrument and mitigation practice or technology change. Having both of these features are preconditions for ascribing causation and quantifying impacts. We also provide checklists and examples of information to include in a policy description, focusing on linking the policy and action to GHG impacts. As a result, the ICAT guidance provides a standard framework for describing policies to ensure key information is consistently reported.

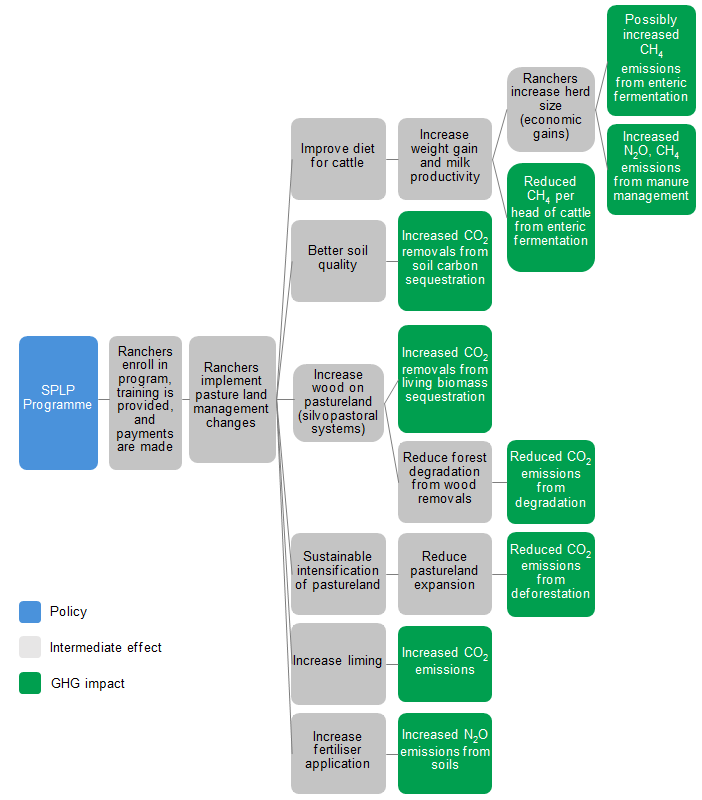

- Instructions for Constructing a Causal Chain

In the guidance, we help users describe how policies and actions lead to GHG impacts using a tool introduced in the P&AS called the “causal chain”. The causal chain illustrates the relationships that drive GHG impacts. It begins with the policy and the inputs needed to enact it, followed by the cascade of intermediate effects that occur to reach the ultimate intended GHG impacts. These effects must also include those that lead to unintended GHG impacts. The causal chain is a powerful tool and has other important uses described below.

To help users understand how to construct a causal chain, the draft guidance includes a hypothetical policy example, shown below.

How is a causal chain useful?

- Causality: As a descriptive model, a causal chain displays the case for causality between a policy and GHG impacts. If you cannot logically connect the policy to GHG impacts via intermediate effects, then chances are the policy has no bearing on the GHG impacts. The completeness and integrity of a causal chain can be informed by stakeholders and evaluated by technical review, serving as a standard framework for construction and critique of causality.

- GHG assessment boundary: The causal chain shows unintended pathways that may ultimately frustrate the positive GHG impacts of a policy. This process of recognition is essential for establishing the GHG assessment boundary. It is more difficult to standardize a policy-level GHG assessment boundary than a project-level boundary, given the wide-ranging possibilities of policy details and implementation circumstances. The draft guidance provides a method for identifying the GHG assessment boundary, consisting of principles and considerations for determining whether a GHG impact should be included in the quantification of GHG impacts. The value of having these principles and considerations is that they provide a framework for both construction and critique of the GHG assessment boundary.

- Projections and assessment: The causal chain can be used to predict the “best case” ex-ante policy scenario (I’ll say more about this in the next section) and for evaluating an ex-post GHG impact assessment. Reviewers can use evidence to assess the extent to which relationships and effects predicted in the causal chain occurred and led to measured GHG impacts.

- Indicators: One final use of the causal chain is to identify policy performance indicators. Indicators are another potentially powerful tool for tracking progress and ambition of NDCs. These are intermediate effects that can be readily tracked during the policy implementation period to monitor policy effectiveness. For example, in the causal chain above, livestock weight gain and milk production appear to be good performance monitoring indicator candidates. It is data that are routinely collected and, according to the causal chain, linked directly to dietary changes and CH4 emissions per head.

- Method for Assessing the Likely Implementation Potential of a Policy

A serious risk in carbon accounting is to overestimate the GHG benefits of policies. Overestimating the effectiveness of policies means we run the risk of underachieving NDCs and fail to achieve the necessary level of GHG reductions.

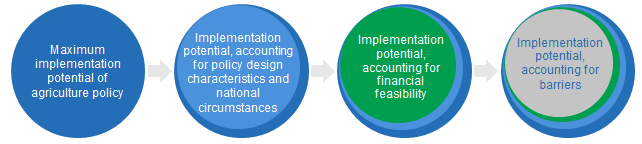

Therefore, another aspect of assessing NDC ambition is ensuring we are evaluating a plausible ex-ante policy scenario. The agriculture and forest ICAT guidance provides a method for systematically refining the ex-ante policy scenario into a “most” plausible policy scenario. The method accounts for policy design characteristics as well as national circumstances, financial feasibility, and other types of barriers.

I’ll give you a sense of how it works. The first step is to use the causal chain to infer the “maximum implementation potential,” which means you assume the policy is implemented as planned, i.e., on the timeline, with the resource levels, and at the geographic scale envisioned. So, for example, you estimate how many hectares of land will be covered by a policy if everything goes as planned. Next, you apply screening assessments to produce a refined “likely implementation potential,” which is the scenario you use to estimate GHG impacts. This process is illustrated below.

Walking through the screening steps may unearth unforeseen design flaws, financial issues, and major barriers. Discovering these challenges before policies are implemented can allow us to address barriers and adjust expectations for GHG benefits.

This method deviates from traditional carbon accounting. It merges estimating activity data with policy and economic analysis. It will take particular and diverse skill sets, and broad engagement of experts and stakeholders to implement well.

The resulting deeper understanding of effective policies can help policymakers translate NDC ambitions into reality.

Looking Forward

The draft agriculture and forest ICAT guidance documents are a solid start on the type of GHG accounting framework we need to effectively track NDCs. The elements are there for standard, transparent, and credible MRV with practical methods for: describing policies, illustrating and analyzing causality, and developing plausible policy scenarios. And, there is more in the drafts than I have discussed here.

As drafts, I am certain there is room for improvement. I encourage you to share your critiques. The agriculture and forest sectors each have their own documents, but they are similar. Pick one and read it. And, then, I urge you to submit comments on the drafts (directions below). Reviewers will be acknowledged in the final versions. As carbon management professionals, together on this new frontier, this process is your gateway to engage and shape the future of climate change policy.

Directions for Submitting Public Comment

Follow directions on the ICAT Public Consultation website to submit comments. This public consultation period is open for 60 days, from 26 July to 25 September 2017.

Hi Katie. this is a very interesting initiative and I think will be helpful. One extra item I would add to Section 3, Method for Assessing the Likely Implementation Potential of a Policy, is an analysis of overlapping policies. I’m working on a project in the Philippines to help the government (Climate Change Commission) do an economy-wide assessment of mitigation potential and we are finding quite a bit of overlap and interaction between policies (within sectors and across sectors). the timing of their implementation also influences the extent of this overlap. Since mitigation options most often are assessed within each sector, this has come as a surprise to policy makers. it turns out that all policies when combined reduce less emissions than expected. Not sure if this analytical step is inherent in one of the 4 circles already, but I think its important enough that it should be called out specifically. Good luck with this effort. Many regards Jette

Hi Jette: That’s a great point! Your experience with the project for the Philippines illustrates the real potential complexity of this type of analysis. Yes, there is guidance for determining whether to assess individual policies or a package of policies (with this later option fitting the scenario you described), and guidance for how to characterize the types and degrees of interactions between policies (e.g, reinforcing or overlapping). This step comes before the analysis of likely implementation potential. Even so, I think it will be quite challenging to analyze likely implementation potential for a package of policies. Thank you for sharing your experience. Best, Katie

Helpful information. Fortunate me I discovered your web site

by accident, and I’m shocked why this coincidence did not happened in advance!

I bookmarked it.