This is the first in a two part series about voluntary reporting of corporate emissions inventory data. (For this series, voluntary reporting refers to emissions disclosures outside of regulatory reporting requirements for programs such the U.S. EPA’s Mandatory Reporting Rule or the E.U.’s Emissions Trading System.) This post is intended as the start of a conversation about the availability and quality of emissions data found (or not found) on company websites. Part 2 will explore the number of companies reporting. You are invited to join this conversation through the comments section below.

I consider myself privileged to have attended various sustainability and standards-related conferences, workshops, and events over the last few years. Most include a segment that goes something like this:

“X% of [unspecified qualifier] companies are now reporting their GHG emissions!”

or

“Y% [usually 70% or 80%] of reporting companies exhibit ____[Some positive attribute].”

Listening to these presentations, most of the audience seems content with the state of corporate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reporting.

I am always pleased to celebrate the people who have done the hard work of reporting. But recently I have been intently working with and studying the data in corporate sustainability and GHG inventory reports. This research has left me with a deep sense of unease. Are corporate GHG inventories really in as good shape as the impression one gets from these events and promotions?

My conclusion after deep investigations is that, unfortunately, they are not.

What leads me to this conclusion? First, let’s try something you can easily do yourself and look for some examples. You may be surprised, but greenhouse gas inventory reports from corporations are rarely made public. They are almost impossible to find! Rare as in my Google query for “GHG inventory report” (everyone’s will be different due to Google’s use of personalization and location to customize search results) produced only 2 reports in the first 10 pages of results (2/100). One of those was the GHG Management Institute’s report. Failing here, I tried the alternative path of picking 2 or 3 of the corporations I admire for their GHG work, going to their sites and searching for GHG inventory reports. No luck.

Remembering that my mindset is GHG emissions centric and the rest of the world is not, I recalibrated my search to look for sustainability reports instead. Public sustainability reports are much more plentiful. Some of them have GHG data inside.

Mining corporate sustainability reports for GHG data is something I have a great deal of experience doing: I’ve personally inspected hundreds of corporate sustainability reports and directed teams that have reviewed thousands more. After looking at all these reports some trends begin to emerge.

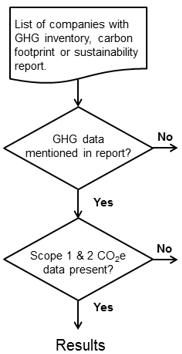

Here’s the approach I used to gather data and form the opinions shared here. I encourage you to try it:

|

Get a list of companies, for example, the global 500 corporations. (Enter global 500 companies in your favorite search engine.)Generate a random number to use as an index on the list. For example, enter ‘=randbetween(1,500)’ into a cell in Excel. Look up the company that corresponds to the number on the list of companies.

Find the company website and click around until you find the GHG inventory, carbon footprint or sustainability report. When you find the report, open it up and look for any GHG data. If any GHG data is present, look for Scope 1 and Scope 2 CO2e. Record the results. Repeat. In this procedure, I seek a public disclosure of GHG data by the company on the company’s website in a GHG inventory report (very rare), a carbon footprint report (uncommon), or a sustainability report (common). In the discussion that follows, I refer to all casually as sustainability reports. |

Sustainability Reports are Beautiful. Sustainability reports are beautiful eye candy. They have lots of color, graphics, and images that evoke positive feelings. But while these reports are high on aesthetics, they generally fall short on numbers and methodological transparency.

The quality of GHG disclosure is poor. I chose quantified Scope 1 and Scope 2 CO2-equivalent emissions as a proxy for quality of disclosure. In preparing a corporate inventory, Scope 1 and Scope 2 are the most straightforward numbers to calculate. Disclosing GHG data at this level of detail requires reference to fundamental emissions accounting principles and is foundational for basic GHG emissions performance indicators — the minimum quantities for measuring progress over time and for making comparisons.

If you go through a list of a few thousand corporations with sustainability reports, you will find only a small fraction report data on emissions. In my experience, of those that report anything numerical on GHG emissions, only about 30% will disclose data for Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions. 30% is an approximation from a non-statistical sample (in 2012) of websites and 2011 sustainability reports of several thousand companies. Spot checks in 2013 of 2012 reports show some improvement from ~30%, but a substantial shortfall remains.

Contrast my 30% hit-rate for GHG data with generally accepted quality expectations for financial data. Like anyone who has had the most basic introduction to business reporting or accounting course, when looking at corporate financial reports for publicly traded companies I expect to find revenue, costs, profit or loss, and assets & liabilities 99.99% of the time.

Had my proxy for quality disclosure been the complete set of reporting requirements specified in the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard, rather than only Scope 1 and 2 emissions data, the quality disclosure rate would have been much lower than 30%. For example, the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard requires data by Scope on individual GHGs separately and CO2-eq for each. Data at this level of detail is even rarer in the population of sustainability reports. Recall the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard was released in 2001 and it is foundational to many reporting programs and for reporting to various registries.

Where does public disclosure of GHG data go wrong? If a company has done a proper GHG inventory, they will have developed Scope 1 and Scope 2 data. So why leave them out of a sustainability report? Is this lack-of-quality GHG data an accounting problem or a disclosure problem? (Please feel free to share your opinion in the comments.)

I acknowledge the possibility that corporate GHG inventory data may exist, but I or my teams simply could not find it – either by computer-aided search or by human-powered examination of websites and reports.

It may be that companies are voluntarily reporting GHG data to registries, but not including data at the same level of detail in their sustainability reports. If this is the case then my tastes for transparency are not being satisfied. I am of the opinion that GHG data should be reported by a company directly as a first party disclosure. Registries are third parties. I am pleased if companies choose to publicly disclose AND report the data to CDP, The Climate Registry, and others, but I want first party data that I can track back to a web property owned by the disclosing party. It is not that I think there is any problem with data in the registries. Rather I know there are legal and reputational consequences associated with first party disclosure of material data in any manner other than what the disclosing party knows to be correct. It is possible that others, including the rest of the industry, do not feel the same. Do you?

Another possibility is that inventory data is prepared and published, just not in a manner that is discoverable on the company website. Although unimaginable, it is possible to display a single paper copy of a report on a public sidewalk and truthfully proclaim it to be a public report in accordance with a standard.

All of which is to say that good data, presuming it exists, is too hard to find. Transparency, one of the fundamental principles of GHG accounting, is not being well served when highly motivated people cannot find Scope 1 and 2 data.

I am encouraged when I read chapter 11 of the new GHG Protocol Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Standard that says “Companies shall publicly report the following information … a scope 1 and scope 2 emissions report in conformance with the GHG Protocol Standard…” This provides a welcome requirement for public disclosures when companies seek to report in accordance with the standard and have their inventories verified.

Lack of quality GHG data disclosure is a problem, prompting the UK-based Environmental Investment Organization to say in their recent Carbon Ranking Report:

| “Many companies now benefit from talented, dedicated sustainability staff and are earning top spots for their efforts, but the overall picture globally remains poor. Many companies go to great lengths to collect and analyse detailed greenhouse gas (GHG) data, only to fail at the last hurdle with simple errors in data presentation, such that a member of the public cannot decipher what the data means when set against the accepted GHG Protocol standard, the most widely used international accounting tool for GHG emissions. Unless all companies are reporting and presenting their GHG data in a clear and uniform manner, the task of cross comparing against companies becomes all but impossible.” |

Following the report, Reuters proclaimed in a May 2, 2013 headline, “Most firms get greenhouse gas reports wrong.” This is a poor reflection on all of us.

Corporate reporting, and the GHG data embodied in it, gives us a picture of where we stand, our progress and prospects for making necessary and meaningful reductions.

Without quality data, the picture is poor:

Quality accounting and reporting is a predicate for meaningful action to address climate change. Calls to improve data and reporting may seem insensitive when GHG management practitioners gather and celebrate hard work that has been done. But we must confront the fact that good GHG data is not making it into public disclosures.

Each of us has a role to play in improving the picture. Regular readers of this blog have perhaps the most reputational risk at stake when reporting generates assessments from watchdog organizations and the press like “poor” and “wrong.” We also hold the greatest opportunity to educate and influence people practicing corporate communications.

I encourage each of you to seek out the stewards of corporate sustainability reports and explain the merits of publicly disclosing basic GHG data like Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions. Show them the data that should be included. While you are at it, thank them for their leadership and their efforts. Going to the trouble of reporting is a lot of work. Going farther to make sure quality GHG data is publicly reported is essential.

Good data makes the picture much clearer:

* Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Comments