Consumption of natural gas as a replacement for other, more carbon-rich, fuels is a cornerstone of many climate policies. In this blog post, I focus on one issue pertinent to greenhouse gas (GHG) management, which has laid bare an unfortunate reality. GHG professionals are fighting hard to improve their understanding of GHG emissions from the oil and natural gas industry, to keep pace with the industry’s changes in technology, processes and practices. This includes, most recently, GHG emissions from hydraulic fracturing or fracking.

The uncertainty surrounding estimates of methane (CH4) from the oil and natural gas industry is troubling. For it prevents us from being able to answer key GHG management questions, such as: How much does it actually help to switch from coal to natural gas? How do we track a progress towards a nationally determined contribution (NDC) under the Paris Agreement?

I’ll start by examining this issue via the United States, where some of the most extensive efforts have been made to better understand GHG emissions from this evolving industry. The United States has been the epicenter of fracking, which has directed political and regulatory attention to both better tracking and reducing GHG emissions from industry operations.

- Methane (CH4) has 25 times the ability of carbon dioxide (CO2) to trap heat in the atmosphere over a 100 -year time period.

- Per unit of energy, natural gas (56.1 mt CO2/TJ) has a lower carbon content than coal (e.g. 96.1 mt CO2/TJ for sub-bituminous coal and 101.0 mt CO2/TJ for lignite).

In March 2016, the United States and Canada jointly announced their pledge to cut CH4 emissions from the oil and gas industry by 40 to 45% from 2012 levels by 2025 (a pledge recently joined by Mexico as well). Countries stepping forward with commitments like these to reduce methane (CH4) emissions are a welcome contribution to international efforts to reduce global CH4 emissions.

What were U.S. emissions from the oil and gas industry in 2012?

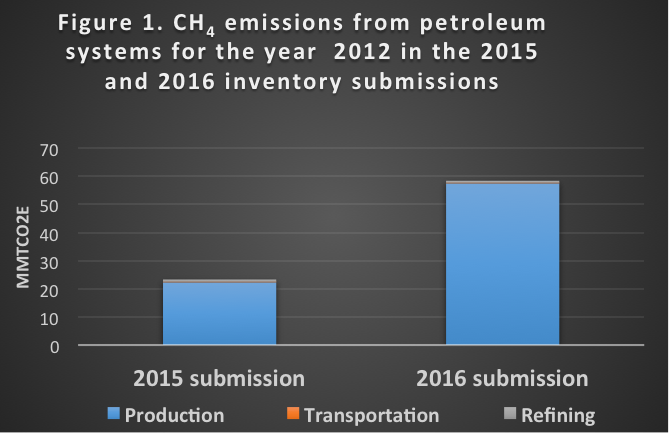

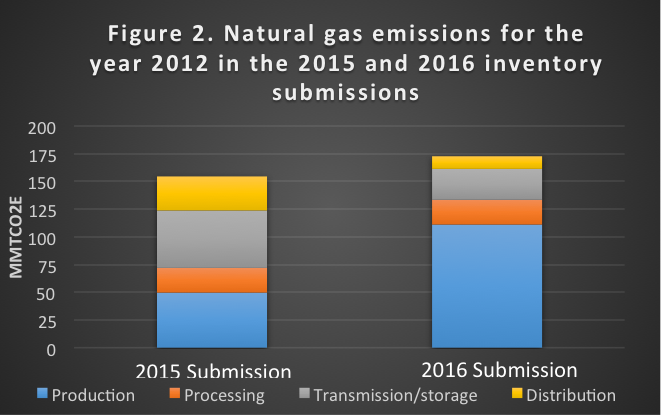

Well, it depends on when you looked. If you rushed to open the latest (2015 submission) statistics available on the afternoon in March when the USA made its joint announcement with Canada, you would find that total fugitive emissions[1] in 2012 from petroleum systems were 23.3 MMT CO2 eq and for natural gas systems 154.4 MMT CO2 eq. But, the annual U.S. GHG inventory submitted to the UNFCCC a month later (2016 submission) provided a different picture. In this most recent submission, the USA estimated 2012 emissions of 58.4 MMT CO2 eq for petroleum systems and 172.6 MMT CO2 eq for natural gas systems, a 151% (Figure 1) and 12% (Figure 2) increase, respectively.

Why the difference between two figures that should have been the same?

Changes in earlier estimates (otherwise known as recalculations) of national GHG emissions are normal, and expected because each new submission is meant to incorporate improved science and data. For example, sometimes only preliminary energy statistics are available at the time an inventory is developed, and these statistics are used as the best available data at the time with full knowledge they will be updated in the next national inventory report. Other times, a key data survey is only available on a biennial basis, and data in the intervening year are held constant or extrapolated until the new data are available. In the case of the USA, the recalculations were conducted to incorporate new, publicly available information on emission factors and activity data from natural gas and petroleum systems. Recalculations of previous emissions estimates are a good thing, and done to reflect improved data and science.

But, the recalculations in the oil and gas emissions estimates for the USA are a symptom of a larger issue of growing importance and attention—our ability to accurately estimate emissions. Recalculations, sometimes large, have become necessary to keep track with an evolving understanding of the latest practices and emissions profile of the industry.

There is much uncertainty about methane emission estimates from the oil and gas industry, particularly on the production side. And the voices expressing concern are growing louder and more prominent. The U.S. government, industry, academia and NGOs are all active and engaged in the conversation. The public is also now beginning to pay closer attention, as stories about methane leakage, like that occurring in the Aliso Canyon storage facility in California, make the evening news and are reported by major media outlets.

All to say, the dissimilarity in the submission figures is likely due to a combination of the historical paucity of information on CH4 leakage from millions of small and large sources, an industry forced to look inward and determine the emissions impact of their operations due to regulatory pressure and pressure from whistle blowers, and an ardent effort by the U.S. EPA to get it right.

So, why should we care?

Isn’t this all just a technical issue that will iron itself out overtime? Why all the fuss?

Because, getting the numbers right does matter, both domestically and internationally.

As the international community rolls up its sleeves to implement the Paris Agreement, we should pay heed to a recalculation from an industry in the USA that is on the same order of magnitude as the total GHG emissions from other developed countries. For example, the recalculation of emissions from natural gas systems were approximately 18 MMTCO2 eq for 2012 while total GHG emissions from Slovenia were 16.6 MMT CO2 eq, and Lithuania 19.1 MMT CO2 eq.

Further, a key means to reducing GHG emissions, evident in many (intended) NDCs submitted by Parties, is fuel switching from coal to natural gas. At a basic level, switching fuel from coal to natural gas has a benefit from a strict carbon perspective—natural gas (56.1 mt CO2/TJ) has lower carbon content than coal (96.1 mt CO2/TJ for sub-bituminous coal and 101.0 mt CO2/TJ for lignite). However, to calculate the actual benefit of this fuel switch, we need to understand the full GHG emissions impact of natural gas, from the well to the power plant.

What do we actually know?

The climate impact related to the use of natural gas reaches beyond the carbon content of the gas. Natural gas is predominantly methane, itself a greenhouse gas. During the production, processing, transmission, storage and distribution, some of this methane can leak from the system. Some leaks are intended. For example, it can be necessary to vent methane to the atmosphere to relieve pressure in the system. This is a safety feature. Some leaks are unintended, as was the case in Aliso Canyon when, over the course of several months in 2015/2016, 97,100 metric tons of methane (2.4 MMT CO2 eq) were emitted from a single well failure in California.

When considering the GHG benefit of natural gas, one must consider both the emissions from the combustion of the natural gas, as well as the fugitive, vented and flared emissions that happen during the extraction and production process through to the operation of the natural gas meter in your home.[2] According to the Environmental Defense Fund, new natural gas combined cycle power plants reduce climate impacts compared to new coal plants; as long as leakage rates remain under 3.2%.[3]

Reduction of CH4 emissions from natural gas systems is a powerful mitigation option. There is a breakeven point beyond which emissions of CH4 into the atmosphere from the natural gas system could outweigh the carbon benefit of switching from coal. Fortunately, current data in the national GHG inventory as well as other studies indicate that CH4 emissions from natural gas systems are below the breakeven point, and there are significant, cost-effective, opportunities to reduce upstream CH4 emissions even further.[4]

When natural gas leaks from a well, or any of the hundreds of types of equipment involved in the oil and gas industry, not only is CH4 being emitted into the atmosphere, but dollars are coming out of the pocket of the company, because the leaking methane could have been sold.

The challenge is the ability of a country, at a national level, to track their emissions from the oil and gas industry. And here we get back to the importance of the 18 MMT CO2 eq recalculation by the USA. To track progress at the international level, we must be able to account for emissions from an industry, which in the USA alone includes nearly one million gas wells, over 300,000 miles of transmission pipeline, and literally millions of pieces of equipment that can leak methane. While many of these potential sites of leakage are in remote areas, not manned by personnel.

There are literally millions of potential sources of leaks, vents and/or flares. It can be a herculean effort to merely collect the necessary activity data. The USA has a good handle on these statistics, but for many countries, particularly developing countries, collecting these activity data can be a challenge. Having an accurate number of the equipment counts is fundamental for estimating emissions.

But the activity data are only half of the story, finding the right emission factor to estimate emissions per piece of equipment is the other half. Because emissions are largely the result of unintentional leaks from equipment, the condition and operation of equipment can have a larger effect than just the count of equipment numbers.

Suffice it to say, determining the GHG emissions from oil and gas processes is complex. But, at a basic level, the estimation of GHG emissions from any sector comes down to a simple approach – multiplying “activity data” (e.g., production of primary aluminum) by a factor relating to how many emissions occur per unit of that activity data (i.e., “emissions factor”). So, in the case of the natural gas industry, you might collect data on the miles of pipeline and multiply it by an emissions factor that represents the amount of CO2 or CH4 emissions leaked to the atmosphere per mile of pipeline. In the absence of country-specific information, governments will typically rely on a default emission factor provided by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

But, we know for fugitive emissions from the oil and gas industry, that IPCC defaults have very large inherent uncertainties. For example, use of the default values from the 2006 IPCC Guidelines to estimate CH4 emissions from natural gas systems in developed countries is estimated to yield an uncertainty of around ±100%, while applying those values to developing countries an uncertainty from -40 to +250%. These ranges, generally based on expert judgment, reflect not only the uncertainty inherent in the values themselves, but also the impact of applying these values to different systems in different countries.

There was a seminal study carried out between the U.S. EPA and the Gas Research Institute (GRI) in the early 1990’s and published in 1996.[5] The purpose of the study was to develop a national estimate of CH4 emissions from the U.S. natural gas industry, not to develop default emission factors. However, the emission factors published in the final report started gaining a life of their own, particularly as inventory practitioners were looking to develop GHG emissions estimates at the project, corporate and national level.

The default CH4 emission factors for developed countries contained in the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National GHG Inventories are largely from this earlier 1996 GRI/EPA study, along with some updated data from 2004. The default emission factors for developing countries are based on an even more limited and older set of data.

Which brings us back to those expressing concern. Since the mid-2000’s, the voices of industry, government, and academia have been growing louder; suggesting that the EPA/GRI emission factors being used may no longer be representative of the technologies and practices in the USA. There is also concern that the default factors do not adequately reflect new practices, like fracking of unconventional wells (e.g., shale, tight sands and coal bed methane).

The world is watching

Efforts are underway to collect data and generate new emission factors for the natural gas industry. Since 2012, the Environmental Defense Fund has spearheaded a study, in coordination with industry, academia and research organizations to better understand CH4 emissions, including the best methods for estimating those emissions.

In addition, larger facilities in the oil and gas industry (those emitting over 25,000 metric tons of CO2 equivalent per year) were required as of 2012 to report their annual GHG emissions as part of the U.S. EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program. Under the program, reporters are required to calculate GHG emissions using prescribed approaches such as direct measurement, engineering calculations, or emission factors derived from direct measurement. In most cases, they cannot simply use international default emission factors. Our understanding of oil and gas practices and emissions will grow as additional years of data from this program are reported.

Industry is also calling for continued dialogue to get these estimates right. As part of the public comment process on the 2016 draft U.S. GHG Inventory, the American Petroleum Institute recognized that emerging data from recent field studies have raised concerns about measurement uncertainty, and further recognized the need for a thorough discussion of means of improving the methodology to ensure collection of robust measurement data.

The IPCC itself recognizes that improvements may be needed in our understanding of oil and gas emissions. They held a meeting of international experts in Washington DC in 2013 to discuss the state of knowledge of emissions in the industry. Most recently, in June 2015, experts convened in Geneva to assess where science and data availability have developed sufficiently since the 2006 IPCC Guidelines to support the refinement or development of methodological advice for specific categories and gases. An area identified by experts for improvement was the update or addition of default emission factors of fugitive emissions from oil and gas to reflect current practices and the latest measurement data.

We at GHGMI applaud the efforts to better understand the emissions profile of the oil and gas industry. We urge GHG management professionals to take a moment to see what these studies might mean for improving the understanding of their own efforts. And, importantly, results of these efforts should continue to be made public. Whether it be in the context of national GHG inventories, or for the purpose of making progress towards achievement of NDCs under the Paris Agreement; it behooves the international community to evaluate the appropriateness of data for the development of improved emission factors.

[1] In national GHG inventories, countries separately report combustion-related emissions from vented and fugitive emissions (i.e. intentional and unintentional releases of CH4), consistent with the methods in the 2006 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Guidelines for National GHG Inventories. Stationary and mobile combustion related emissions are often reported at a more aggregated level due to the availability of statistics. In this article, we are referring to vented and fugitive CH4 emissions, as well as methane flaring. [2] Likewise, in such a comparison one should not omit the fugitive CO2 and CH4 emissions from coal mining. [3] EDF calculation based on IPCC AR4 values for radiative efficiency and atmospheric lifetimes of CH4 and CO2. https://www.edf.org/energy/methaneleakage [4] U.S. EPA along with international partners, including the private sector, development banks, and NGOs, as part of the Global Methane Initiative as well as other voluntary and regulatory initiatives, have identified numerous cost-effective opportunities to reduce CH4 emissions from natural gas systems. [5] CH4 emissions from the natural gas industry (June 1996). Co-sponsored between the Gas Research Institute and U.S. EPA. Available at https://www3.epa.gov/gasstar/tools/related.html

Comments