This blog was initially published in english on carboncreditquality.org on March 20, 2024 and reposted with formatting changes.

By Lambert Schneider (Oeko-Institut), Felix Fallasch (Oeko-Institut), Isabel Haase (Oeko-Institut), Hannes Böttcher (Oeko-Institut), Tani Colbert-Sangree (GHG Management Institute), Olga Lyandres (GHG Management Institute), Nora Wissner (Oeko-Institut), Cristina Urrutia (Oeko-Institut), Ankita Karki (Oeko-Institut), Rowan Alusiola, Sophia Lauer (Oeko-Institut), Pedro Barata (Environmental Defense Fund), Darcy Jones (Environmental Defense Fund), Morgan Bomer (Environmental Defense Fund), Olivia Polkinghorne (Environmental Defense Fund).

The analysis presented below is based on the assessment of carbon crediting methodologies [click here for the list of assessed methodologies], not individual projects implemented inline with these methodologies. Individual projects will have varying circumstances and may not experience all of the below identified integrity issues.

Note: if you use the auto-translate tool, translation errors may occur. We recommend reading the blog in its original english.

“The Carbon Credit Quality Initiative (CCQI) has released new scores for the integrity risks of carbon credits from improved forest management (IFM) projects. We find that unrealistic baselines and underestimated leakage are likely to lead to significant overestimation of emission reductions or removals under all assessed methodologies. The likelihood of additionality depends strongly on the forest management practices that are implemented. The sustainable development benefits are more limited compared to most other project types.

The basic idea of improved forest management (IFM) projects is simple: forest owners are rewarded for implementing management practices that enhance carbon stocks. Putting a price on carbon can provide the economic incentives to implement such practices. Improved forest management is also a climate mitigation measure that has significant scaling potential. Globally, planted forests cover more than 500 million hectares, and naturally regenerating forests with some form of management even cover more than 2 billion hectares. [1] In practice, however, we find that this project type has high integrity risks and differs in various ways from other project types.

What is an IFM project?

IFM projects can entail a broad range of activities, including reducing or stopping harvesting, reduced impact logging, thinning, or enrichment planting, among others. Which of these activities are implemented on the ground is often unclear, however. Project design documents often list various general activities, and sometimes identical descriptions are used by different projects. In contrast to most other project types, carbon crediting programs commonly do not require project developers to monitor and document which activities are actually being implemented. Rather, projects can claim credits if carbon stocks are higher than a hypothetical baseline, regardless of whether the envisaged forest management activities were implemented.

Getting carbon credits from producing less timber

IFM projects also differ from most other carbon projects as they can earn carbon credits from producing less timber. In carbon markets, a well-established principle is that projects should provide the same level of service as in the baseline scenario. Project developers cannot get carbon credits from shutting down a cement plant without building a new one, for example. This principle is not applied to IFM projects in which emission reductions may largely accrue from reduced harvesting. This poses high risks for leakage; carbon stocks may be enhanced in one place at the expense of causing emissions at other places as the timber may need to be produced elsewhere.

Mixed picture on additionality

Assessing the additionality of IFM projects is very challenging. Whether an activity needs carbon credits to be implemented depends on many factors: the tree species, the geographic location, or market conditions. Carbon credits are only one variable among many others. We find that the likelihood of additionality depends strongly on the type of activities implemented by projects. Some activities, such as increasing forest productivity, may sustain or even increase revenue from timber production. By contrast, stopping timber production in a forest and instead managing it for conservation is likely to be additional as the project developers no longer have revenues from timber production.

For some activities, such as extending rotation age, the likelihood of additionality varies. In theory, these projects could be additional: revenues from carbon credits can compensate forest owners for delaying harvesting beyond the economically optimal point in time. In practice, many other factors, such as fluctuating timber prices, may influence the timing of harvests. For projects that extend the rotation age by only a few years, it would be very difficult to assess whether such increases are driven by exogenous factors or carbon revenues. For projects with longer extensions of the rotation cycle, additionality is more likely.

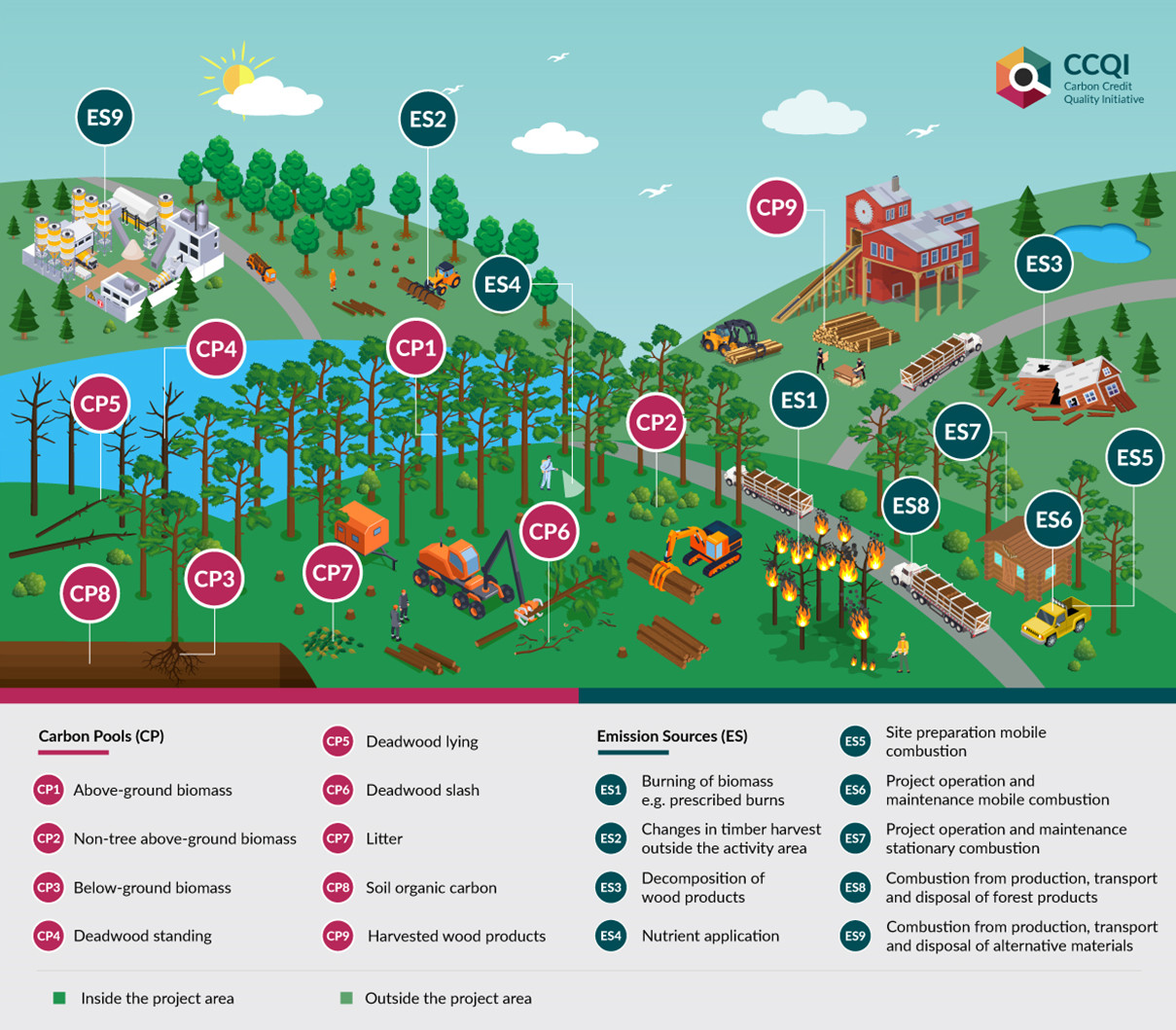

Accounting for carbon: carbon pools and emission sources in IFM projects

Unrealistic baselines

Establishing baselines for IFM projects is associated with high uncertainties. How the management of a forest would evolve over a period of up to 100 years without carbon credits is very hard to predict. This can be affected by many unforeseeable developments: new policies could incentivize enhanced carbon storage (e.g., as part of strategies to enhance removals) or put increased pressure on forests (e.g., by promoting the use of biomass). Timber prices can change over time and climate change may affect future forest management. The impact of these exogenous factors on forest carbon stocks could potentially be much larger than the impact of carbon credits. This challenge is sometimes referred to as a “signal-to-noise issue”: depending on how exogenous factors develop over time, the emission reductions or removals may be hugely under- or overestimated.

None of the assessed methodologies appropriately accounts for this uncertainty. By contrast, we find that methodologies often provide project developers with considerable flexibility in determining baseline carbon stocks. This allows project developers to pick the approaches that result in lower baseline carbon stocks and hence more carbon credits. For example, many projects registered under the California Air Resources Board (CARB) received carbon credits while their forest management practices did not differ from control groups that did not receive carbon credits. [2] Overall, the current methodological approaches for establishing baselines are likely to lead to significant overestimation of emission reductions or removals.

Unaccounted leakage

Since IFM projects may reduce harvest levels, they are exceptionally prone to leakage risks compared to other project types. As with baselines, leakage is associated with considerable uncertainties. Leakage rates reported in the literature vary, depending on geography, forest types, and other factors. We find that carbon crediting methodologies do not appropriately account for this risk. The leakage rates assumed in IFM methodologies (often around 20%) are much lower than in the scientific literature (often around 80%). Moreover, some forms of leakage are not accounted for at all. None of the IFM methodologies accounts for international leakage, but trade of timber does not necessarily stop at national borders. Similarly, methodologies do not account for leakage stemming from the increased production of substitution materials, such as plastics or cement. And some methodologies do not apply a leakage deduction at all if harvest levels decrease by a smaller degree. For these reasons, leakage is likely to be significantly underestimated.

Limited sustainable development benefits

Sustainable development impacts vary depending on the activities implemented within an IFM project. Generally, IFM projects impact only a limited number of sustainable development goals (SDGs), namely SDG 2 (zero hunger), SDG 6 (clean water and sanitation), SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth) and SDG 15 (life on land). For example, shifting from timber production to conservation can strongly contribute to SDG 6 and SDG 15, whereas reduced impact logging has small positive impacts on a few SDGs. By contrast, increasing the productivity of timber production is likely to have an overall negative impact on sustainable development.

Is IFM well-suited for carbon crediting?

Our evaluation shows that the quantification of emission reductions or removals bears the largest integrity risks for IFM projects. We find that all assessed quantification methodologies are likely to lead to significant overestimation. Indeed, quantifying the emissions impact of IFM activities raises fundamental methodological challenges, due to the uncertainty associated with establishing baselines and the “signal-to-noise” issues this raises as well as the large leakage risks if timber production is reduced. For most IFM activities, these challenges are very difficult, if not impossible, to overcome. Therefore, IFM may be better promoted through policies such as subsidies or fiscal incentives rather than carbon crediting.”

[1] Lesiv, M., Schepaschenko, D., Buchhorn, M. et al. Global forest management data for 2015 at a 100m resolution. Sci Data 9, 199 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01332-3

[2] Stapp, J., Nolte, C., Potts, M. et al. Little evidence of management change in California’s forest offset program. Commun Earth Environ 4, 331 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00984-2

Coffield, Shane R.; Vo, Cassandra D.; Wang, Jonathan A.; Badgley, Grayson; Goulden, Michael L.; Cullenward, Danny et al. (2022): Using remote sensing to quantify the additional climate benefits of California forest carbon offset projects. In Global change biology 28 (22), pp. 6789-6806. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16380

[Assessed methodologies] The analysis summarized in this blog is based on work performed by the Oeko-Institut. GHGMI assisted with the assessment of the following offset crediting methodologies’ quantification provisions:

- VM0003 – Methodology for Improved Forest Management through Extension of Rotation

Age, v1.2 - VM0005 – Methodology for Conversion of Low-productive Forest to High-productive Forest,

v1.2 - VM0010 – Methodology for Improved Forest Management: Conversion from Logged to

Protected Forest, v1.3 - VM0012 – Improved Forest Management in Temperate and Boreal Forests (LtPF), v1.2

- ACR – IFM on Non-Federal U.S. Forest Lands

- CAR U.S. Forest Protocol

- CAR Mexico Forest

- ARB U.S. Forest Compliance Protocol

See the quantification assessment sheets for these methodologies by visiting the CCQI website and selecting 1 Robust determination of the GHG emission impact > 1.3 Robust quantification of emission reductions and removals > 1.3.2 Robustness of the quantification methodologies applied and locating the above-identified methodologies from the list.

Comments