Continuing on the theme of widely held fundamental misconceptions in the carbon management community (see previous blog posts here and here), today I am going to write on a matter of terminology I find particularly irksome: the use of the term “counterfactual” in additionality discussions.

Probably one of the most frequently cited assertions relating to additionality is that it cannot be proven because it is assessed against a “counterfactual” baseline. Well, I am here to tell you that this line of argumentation is flawed. Certainly, I admit there is a lot that can and should be improved with how additionality and baselines are assessed under all the existing GHG offset programs. (I have previously elaborated on some potential areas for improvement here.). However, the use of “counterfactual” implies that you cannot prove additionality and that it is a completely unreliable determination. This is a mischaracterization of the actual issue.

In my writings, I have previously argued that the term “counterfactual” has been misconstrued when discussing baselines or additionality. A counterfactual is defined as something that is contrary to the facts or not reflecting or considering relevant facts. But it is feasible to ground the models we use for assessing baselines and additionality using good science and proper causal inference techniques. In other words, observations (i.e., facts) from related cases or experiments can be used to develop models that predict behaviors in similar or identical situations. Assuming the models that produce these predictions are based on rigorous studies, I would argue that the outcomes are not well described as being “contrary to relevant facts.” These models are unlikely to be perfect representations of the case being assessed, but, unless conducted with no consideration of good causal inference methodologies, the assessment of additionality can still be based on observed facts from similar cases and other empirical research. As a consequence, I have previously recommended that the term “unobserved” be used rather than “counterfactual” to describe the baseline used for assessing additionality.

But, my thinking has now gone further. I no longer think that “counterfactual” is simply a misconstrued or misused term for talking about additionality. It is actually flat out WRONG.

Sweating the small stuff

It may seem trivial to work up a sweat over semantics. But in my opinion if there was ever a topic requiring precision and care in how we talk about and conceptualize it, it is additionality and baselines in the context of offsets.

For a proposed project or class of similar project activities, additionality is assessed relative to a predicted baseline, which represents a scenario under identical conditions except for the absence of the recognized intervention created by the offset program (e.g., such as the price signal from the potential to earn offset credits). Although it may be possible to observe the behavior of an actor under the influence of an intervention and another similar actor under near identical circumstances where the intervention is absent, it is rarely possible to simultaneously observe the behavior of the same actor under the same conditions both with and without the intervention present.

In a typical GHG offset project cycle, the assessment of additionality follows the development of a predictive baseline model. This assessment occurs at the proposal stage, prior to a project’s implementation. Therefore the baseline for this purpose is not a backward looking counterfactual but instead a forward-looking prediction. Although additionality is characterized as an assessment against a counterfactual baseline throughout the literature on CDM and other GHG offset programs, it remains that something that is set in the future and cannot accurately be considered a counterfactual. In other words, at the time it is actually conducted, additionality is not a counterfactual assessment, but rather it is a prediction.

In contrast to the forward-looking additionality assessment, a GHG offset project’s emission reductions are calculated against a backward-looking counterfactual baseline.

The simple lesson here is: stop calling additionality a counterfactual. It is not.

Baseline bingo

So now that we have identified two applications for baselines (i.e., assessing additionality ex ante and calculating emission reductions ex post), we can think about another question: for a given project, should the two baselines used for assessing additionality and calculating emission reductions be the same and what are the implications of them being different?

[Warning: the following discussion is probably best treated as an advanced topic for more intellectually ambitious readers. So, just to be clear, you have been warned.]

First, it is critical to understand that if a project proponent lacks certainty in the baseline that will be used for determining additionality and calculating emission reductions for their proposed project, this uncertainty will affect their perception of the strength of the offset program intervention. In other words, the more uncertainty in the baseline that a project proponent perceives, the less likely the project proponent is to change their behavior and as a consequence, their proposed project is less likely to be additional.

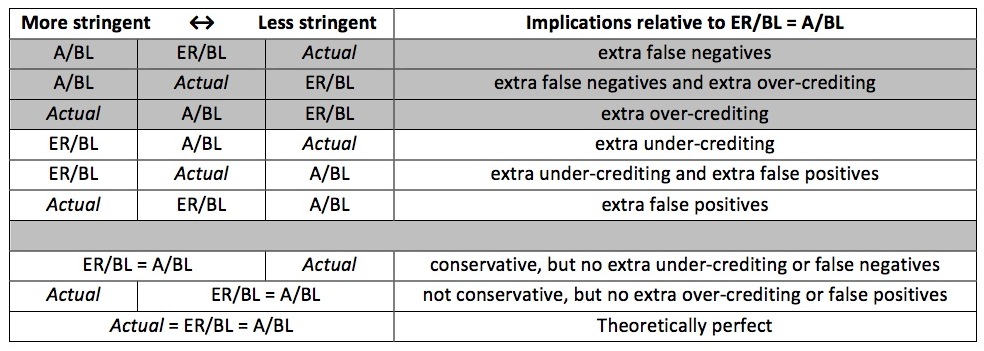

Beyond having this negative feedback on the perceived strength of the offset program intervention, this uncertainty will also lead to one of a number of undesirable outcomes that will reduce the credibility of the overall process. The table below summarizes these outcomes. In the table, A/BL is the baseline used for assessing additionality and ER/BL is the baseline used for calculating emission reductions. Actual is the true baseline, which we do not observe, yet it does exist, theoretically. As shown in the table, not maintaining consistency between A/BL and ER/BL effectively assures that there will be a higher error rate in additionality determinations and/or crediting relative to setting them equal.

Table: Possible outcomes with respect to stringency of baselines for additionality determination (A/BL) and emission reduction crediting (ER/BL).

So although we could play games with baselines to try and make them more conservative, thinking we are improving the environmental integrity of the offset program, these efforts are likely counterproductive (from a game theory perspective). Project developers, knowing that their ability to earn offset credits has been altered, will then simply alter their behavior accordingly. Instead, we should focus our efforts on coming up with the best baseline prediction we can (i.e., getting our prediction as close to actual as practical) and using that single baseline for both ex ante and ex post applications.

Comments