COP22 Outcomes by the Numbers

The UNFCCC COP21 in Paris last December was fast-paced and over-the-top, like a holiday blockbuster. The negotiations wrapped up nicely with a holiday happy ending called the Paris Agreement.

If Paris was the last year’s feel-good-movie of the season, COP22 in Marrakech was like the beginning of a legal drama. The intricate plot was impossible for any one person to follow. Even the outcomes were uncertain without some serious plot tracing effort.

Even for those of us on the ground in Marrakech, the rhythm of the negotiations felt stilted, too fast and too slow at the same time. The Paris Agreement had entered into force just days before, years earlier than expected on an energized tide of international political support. Then to everyone’s shock, after day two of negotiations, the United States’ quirky electoral system selected Donald Trump as president, a climate change denier and conspiratorialist who threatened to tear up the Paris Agreement. Countries spoke loudly and with excitement about maintaining the “spirit of Paris.”

In the negotiating trenches, however, this spirit seemed to translate little into acceleration in the discussions. The necessarily technical talks were moving at a pace that made snail races look fast. The dozens of negotiating streams left one’s head spinning.

With COP22 now concluded, we are left asking: Did the Paris Agreement charge ahead with unstoppable momentum, or has it begun to fizzle out?

In this blog post, we look at COP22 by the numbers to assess the current health status of the Paris Agreement.

Mandates on the table at COP22

Most of the details of the new climate regime were left unsettled at COP21 in Paris. Though the Paris Agreement has now “entered into force” that does not mean implementation has yet begun.

The Paris Agreement and its accompanying decision text lay out a blueprint for the new international program on climate change. In this are some 91 mandates with timelines, representing rules to be elaborated and choices to be made about how exactly to pull together the new climate framework. For example, what are the rules for the new carbon trading market mechanism? How much do countries need to communicate about capacity-building support? And so on.

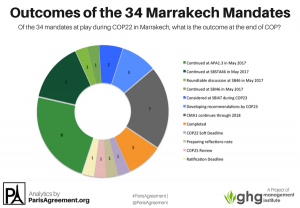

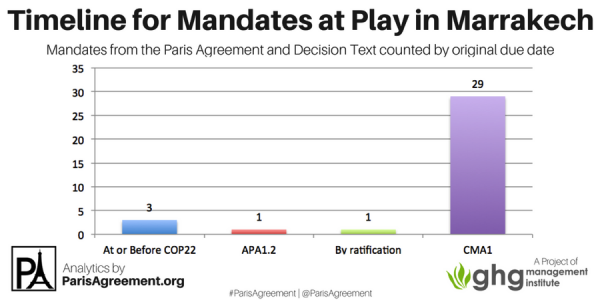

On the heels of our ParisAgreement.org work, tracking negotiation text outcomes at COP21, we mapped the topography of the Marrakech outcomes. Before landing in Morocco, we identified a total of 34 mandates “at play” in Marrakech, 29 of which were triggered by the Paris Agreement’s early entry into force. These 29 mandates are listed with original deadlines of “at” or “by” CMA1, which is the first meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement.

– “At or before COP22” describes those items that explicitly mention a November 2016 deadline at COP22 in Marrakech.

– “APA1.2” refers to decisions made by the APA at its second session (November 2016).

– “By ratification” applies to individual Parties and sets a deadline by the time they ratify the Paris Agreement.

– “CMA1” refers to mandates with timelines of “at” or “by” CMA1, triggered by the early entry into force of the Paris Agreement. At COP22, these were interpreted as having a November 2018 deadline.

- The UNFCCC structure involves many different “bodies” tasked with decisions on the international climate change policy framework. The Paris Agreement and accompanying decision text deliver mandates to a number of bodies.

- COP: the Conference of the Paris, held each year, “the Supreme Body” of the UNFCCC that includes all Parties (countries).

- CMA: the conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement, first held this year, and includes only those Parties that have ratified the Agreement.

- Secretariat: the UNFCCC secretariat, who manages the UNFCCC process.

- CMP: the COP for the Kyoto Protocol, held annually.

- APA: the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Paris Agreement, a subsidiary body tasked with developing much of the “Paris rulebook”.

- SBSTA: the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technical Advice, one of the original subsidiary bodies under the UNFCCC, tasked primarily with scientifically-relevant matters.

- SBI: the Subsidiary Body for Implementation, one of the original subsidiary bodies under the UNFCCC, tasked largely with budgetary and administrative matters.

- Parties: countries belonging to the UNFCCC.

To understand the mandates at play, we mapped these by timeline, topic, actor, and legal nature of the language (available here).

With the Paris Agreement’s 2016 entry into force, years ahead of the original anticipated 2020 date, no one realistically thought all 29 of the 34 CMA1-related mandates would be resolved in Marrakech. The realistic hope was instead that we would make significant progress on as many of the 34 mandates at play as possible.

What progress was made at COP22? Outcomes by the numbers

The news of the U.S. elections rattled COP on the third morning. The moment came early enough in the COP22 negotiations that talks could have collapsed in disagreement. Yet, they did not.

After completion of two weeks of negotiations, where do we land with the 34 “moving pieces” of the Paris Agreement at play in Marrakech? And what does this tell us about the direction of the international climate regime?

To answer this question, we categorized COP22 outcomes with respect to these 34 mandates, based on the UNFCCC secretariat progress tracker and personal communications with those directly involved in the negotiations (click figure to enlarge):

First, overall progress can be summarized as follows:

- 15 of the 34 mandates will continue at the negotiations in May session of negotiations, primarily in the APA and SBSTA tracks. COP22 outcomes for the APA involve “informal notes” by co-facilitators, containing options and key questions for various agenda items, such as transparency guidance. Ideally, these “note” will help guide future discussions.

- 5 mandates are on hold until COP23 in November 2017, either for further negotiations or with draft recommendations. The three items with draft recommendations include: adaptation matters, public awareness, and Nationally Determined Contributions (climate pledges) timelines, and are “nearly” complete.

- 7 mandates have been “punted” by expanding CMA1 into three parts over a period of three years that conclude during COP24 in 2018. This unadjourned “first CMA” is a workaround to provide negotiators with a reasonable deadline to conclude the Paris Agreement rulebook. All 7 of these mandates build off more technical decisions.

- 3 mandates were completed in Marrakech, which we explore below.

From the 10,000 meter view, we see that the negotiations are moving forward.

Tracking 2017 Party Submissions Timelines

Of the 17 mandates whose outcome involves continued negotiations in 2017, 15 involve a timeline for Party submissions before the May 2017 intercessional meetings (and some also allow non-party stakeholder submissions). This continues the extensive request for country submissions that led some to wryly refer to COP22 as the “COP of submissions.” It also sets the stage for an demanding amount of work for Parties to develop positions and recommendations on a large number of complex issues.

Topics for submissions include features of NDCs and NDC accounting, guidance related to adaptation in NDCs, inputs and modalities for the Global Stocktake, and other matters, chronicled below (click figure to enlarge):

The extensive request for submissions before the 2017 intercessionals again points to a movement forward on all fronts. It shows a slow, but properly consensus-based approach (the “Party-driven process” in UNFCCC parlance) needed to build a strong foundation to the Paris Agreement. Parties are not giving themselves a year to regroup in the wake of a deeply unfortunate election outcome. They are not waiting to gauge the actions of a new president. They are continuing the work at pace.

What were the three “completed” mandates? What does this tell us about the direction of the negotiations?

We’ve classified three of the mandates from Marrakech as “complete” based on the UNFCCC secretariat progress tracker. These three mandates are:

- direction on whether the Adaptation Fund will serve the Paris Agreement,

- how the IPCC will inform the Global Stocktake developed in Paris, and

- the terms of reference for the new Paris Committee on Capacity-building.

-

The Adaptation Fund will serve the Paris Agreement

Adaptation Fund (AF) was originally operative under the Kyoto Protocol. Paragraph 60 of the COP21 decision text tasks Parties to agree on whether to allow the Adaptation Fund to serve the Paris Agreement.

In Marrakech, Parties decided that the Adaptation Fund will serve the Paris Agreement. Many developing countries rallied for this and pushed back against the opposition of many developed countries. This indicates that Parties are able to reach agreement on contentious issues and old structures are being efficiently reused.

Note: Institutional arrangements linking the AF to the Paris Agreement will be decided by a joint session between COP, CMA, and CMP (COP for the Kyoto Protocol) in 2018.

-

IPCC Assessment Reports will inform the Global Stocktake

Paragraph 100 of the COP21 decision text essentially tasks SBSTA with providing advice for aligning the global stocktake with the work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). This actively encourages the Global Stocktake, which is ultimately a political process, to be based in the world’s best climate science.

This COP22 outcome confirms that the IPCC assessments will inform the Global Stocktake, particularly through lessons learned, dialogue between IPCC and countries, and special SBSTA-IPCC joint events. This decision specifically speaks to the sixth IPCC assessment report, which will be released piecemeal over 2018 to 2022, with the synthesis report available “as soon as possible in 2022,” in time for the first Global Stocktake in 2023. The science will talk and the COP will listen.-

Launching the Paris Committee on Capacity Building

The Paris Agreement and accompanying decision text involve two major outcomes for capacity building:

- the Global Environmental Facility’s Capacity Building Initiative for Transparency (CBIT), a new funding mechanism, and

- the Paris Committee on Capacity-building (PCCB), a panel tasked with strategic guidance for capacity-building.

At COP22, the Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI) developed the terms of reference (ToR) for the PCCB. The ToR is short, simple, and mostly administrative. The first session of the PCCB will be held in May 2017, at the sidelines of COP, with the theme “capacity-building activities for the implementation of nationally determined contributions in the context of the Paris Agreement.”

During the negotiations, the PCCB ToR was celebrated as a major outcome. We can view the celebrated launch of the PCCB either optimistically or pessimistically. It’s possible there was nothing more substantial to celebrate. But we can also see it as a statement that countries continue forward with fresh climate action. And we can see the PCCB as an important “bipartisan” win between traditional developed and developing country groups, with countries of all types participating as they are able.

If this capacity-building panel is the vanguard for progress on climate change, it suggests potential high-profile attention on developing country capacity. It creates an interesting possibility that COP23 in 2017 could host the “Capacity-building COP,” a COP fundamentally about cooperation between the global north and south to empower greater climate action.

Even-Keeled Progress

What are the outcomes of COP22? Future negotiations on a slew of topics, informal notes marking progress, and timelines for country submissions. Three mandates are completed and three others nearly complete.

Clearly, the outcomes of COP22 do not have the same explosive appeal as the Paris Agreement entering into force. But we see the front is still advancing forwards.

Yes, there are possibilities brewing on the geopolitical stage that could upset the steady the progress made so far. But the “mood of defiance,” described by Axel Michaelowa in his immensely useful COP22 outcomes summary, suggests that other countries will not let the President-Elect of the United States make or break the Paris Agreement. After his election, negotiations did not stall. Parties still agreed to finalize the Paris rulebook by COP24 in 2018.

An across-the-board scan of COP22 outcomes indicates that legal and technical negotiations are continuing ahead. For a more in-depth analysis, we could look at the informal notes coming out of the subsidiary body meetings to observe the progress being made on standardizing NDCs or designing the Global Stocktake to ascertain global progress on climate change.

What we see there appears healthy as well. Parties are making steady headway, considering a range of possibilities, asking smart questions, and providing future input through upcoming submissions.

It’s too soon to call for sure how the development of the Paris rulebook will proceed. But moving towards the May 2017 intercessional, we can get a sense of how much political will exists to finish the Paris Agreement rulebook and secure an international framework for climate action as we see how many—and which—Parties thoughtfully express their views.

In the face of unnerving political developments, the international climate policy negotiations have neither shut down, nor rushed ahead in haphazard panic. For now, they proceed at pace.

Comments