“Can USEPA’s new power plant ‘rule’ break our climate logjam?”

Like many of you, it is my ardent hope that the answer to this question is yes. Yet, I am skeptical.

The rule I’m referring to, of course, is the new regulation proposed in the USA to address greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from power plants. Since you have found your way to this post, I am making the educated assumption that you may have already come across some coverage of the issue. Last Monday was, after all, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (USEPA’s) kick-off of the comment period for the proposed regulation (“rule”).

Since there has been no lack of news and commentary on the subject, with this post I am going take a slightly different approach: help those already working on climate change issues better understand what to expect from this policy. I’ll provide what I think is a nuanced perspective on the details of the policy, while highlighting some intricacies of the American regulatory rule-making process for our international readers.

What is the policy supposed to do?

It is hardly controversial to suggest legislative politics at the national level in the USA are gridlocked. Indeed, some have gone much further, concluding that the political system at the national level in the USA is broken. Yet, as dreary as this observation may read, by allowing parts of government to act on their own at times, the federal model can provide glimmers of sunshine.

Last week’s action by the Obama administration to propose the direct regulation of GHG emissions from U.S. power plants without the approval of Congress exemplifies this division of powers, leading to the confusing situation of the U.S. government simultaneously opposing and proposing climate change regulation.

Moving beyond the system of government that has allowed this apparent contradiction, let’s take a practical look at what was actually announced last week by the USEPA:

1) This is but the start of a long rulemaking process. Last week’s announcement was of a proposed – and as yet incomplete – “rule”. It still has several stages to complete before the regulation is implemented and enforced. (I will walk you through these stages in the next section.)

2) Absolute targets are valuable, but mind the base year. Electricity generation accounts for about 38% of total U.S. CO2 emissions (or 32% of total GHG emissions). The advertised environmental effect of the proposed rule is to reduce CO2 emissions from the electric power sector by 30% below 2005 levels. However, it is important to recognize that emissions from the sector are already down about 13% since 2005—a decrease due in large part to the major economic recession and an expansion in domestic natural gas supply. Put in more easily comparable terms, the target is roughly a 17% reduction by 2030 from today’s level. Unfortunately, even this smaller reduction is not assured for reasons I’ll discuss below. Why choose to frame the policy target in terms of a 2005 base year? The reasons seem to have been largely political.

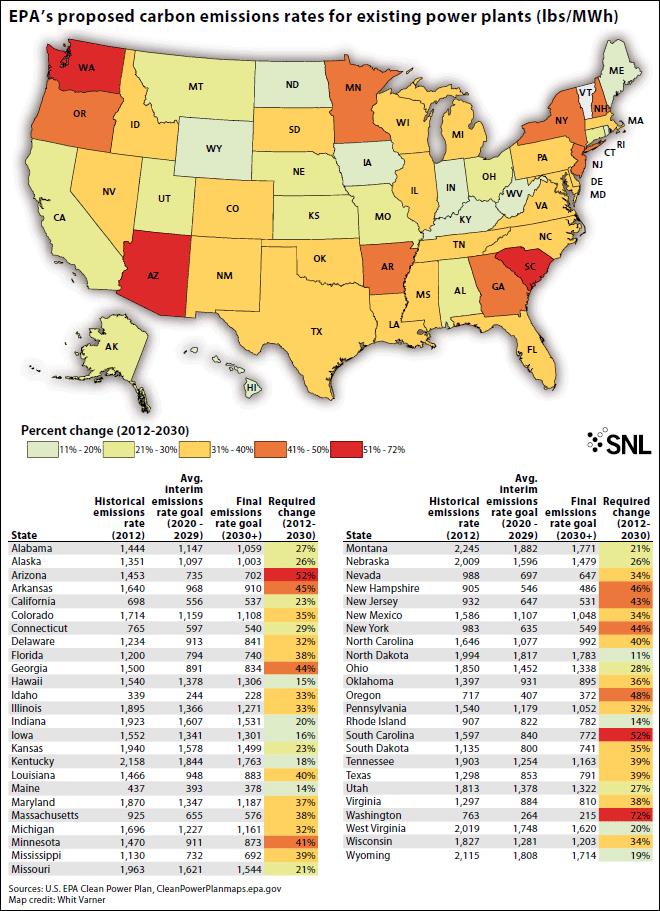

3) A State-by-State approach. Percentages aside, what the USEPA has actually proposed is a set of CO2 emission intensity targets (tonnes CO2/MWh) for the power sector for each State in the USA. (*Excluding Vermont and the District of Columbia, which have no fossil fuel-fired power plants.) These intensity targets will be set over two time periods: the first an interim target to be achieved as an average over 2020 to 2029 and a second target to be achieved in 2030 and beyond. Each State will be obligated to come up with its own mix of policies to achieve its target. Proposed targets were calculated by the USEPA incorporating each State’s capacity to improve its CO2 intensity of generation of its existing fossil fleet along with its potential for renewable generation and expanded demand-side energy efficiency.

4) An illusory absolute target. In contrast to much of press reporting, the proposed rule does not set an absolute target for a 30% reduction or use 2005 as a base-year. The 30% number is an estimate of how much USEPA expects emissions to be reduced if all States complied with their emissions intensity target. Further, actual emissions in 2030 might be higher or lower depending on future electricity demand, population, or economic growth. And instead of the year 2005, each State’s intensity target was actually built using data on existing fossil fuel power plants over the period 2002-2012 along with assumptions about the potential of other measures, including renewables and energy efficiency, in the State to reduce emissions starting in 2017. Each State’s target also makes more sense once you consider that USEPA excluded existing large hydropower facilities from the starting carbon intensity for each State. For example, Washington State in the Pacific Northwest gets almost all its electricity from hydro and has only one major coal-fired power plant that is already targeted for closure. So, it is required to make a steep reduction in carbon intensity. The caveat here is that there is still work to be done to untangle and analyze the assumptions USEPA has made in setting each State’s target. All in all, the regulation will nationally affect about 1,000 power plants.

Note: Data in table have not been verified. Further, there are still numerous yet to be answered questions regarding USEPA’s calculation of State targets. Therefore, treat numbers with caution.

4) 49 flavors of climate policy. Under the proposed rule each State will have to choose and implement measures to meet its target. The national government prescribes no specific policies or measures. Instead, it suggests four broad types of measures: i) increasing the efficiency of existing fossil fuel power plants; ii) switching to less carbon intensive fuels; iii) expanding use of renewable and zero emitting power sources; and iv) demand reduction through energy conservation and efficiency measures. An important accounting note to remember in the context of this rule: reducing electricity demand will not necessarily improve the emissions intensity of existing fossil fuel plants. It will instead only cause them to generate less electricity. So, for States to be credited with renewable energy or energy efficiency improvements, they will have to convert this data to an equivalent intensity improvement for fossil plants or convert from a rate (emissions per MWh) to a absolute mass basis (total tonnes emitted).

In its essence, USEPA’s proposed rule is nothing more than a numerical reduction target for each State. The expected result will be a patchwork of different rules and programs across the country. Some will experiment on their own, while others will attempt to join existing emission trading programs in California or the northeastern States (RGGI).Some will attempt to comply by expanding existing renewable mandates and energy efficiency efforts. Some are liable to drag their feet at every step of the way, refusing to comply and putting up a fight in court and on political stages. The potential for regulatory complexity, if not chaos, is a real danger.

| Are GHGs pollutants?There is an ironic origin story to this week’s policy announcement that I was reminded of by our Board chairman, Wiley Barbour. The legal foundation for this proposed power plant rule was partly established by an earlier court ruling on a challenge to new national automotive fuel efficiency standards. The legal argument against those standards was that GHGs were not pollutants. This legal strategy backfired when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that GHGs were air pollutants, making them newly subject to the aging U.S. Clean Air Act. So, without the lawsuit by groups fighting GHG standards on vehicles, we might not have this rule for power plants being proposed now. |

So what happens next?

The June 2nd release of the proposed rule is just the beginning of a lengthy regulatory timeline. The upshot is that we are unlikely to see implementation of additional emissions reduction measures because of this policy for years. Nonetheless, I think that this policy shift in the USA does have the potential to make a significant impact. Here is what to expect:

Year 1: Finalization

The U.S. EPA will spend the next year gathering comments on the proposed rule from the public, industry, and State governments. It will then have to address comments and finalize the rule. USEPA expects the rule to be modified following what will likely be an intense and bitter public perception battle. The agency’s goal is to have a final rule in June 2015. The track-record for finalizing rules this big on time, though, is poor. Expect delays and a potentially weakened or delayed final rule as a consequence of intense lobbying.

Year 2: Litigation

After the rule is finalized, then legal challenges will be filed. Although most challenges to USEPA authority in these types of rulemaking matters have failed in recent years, the litigation process will still consume time and agency resources. The resulting legal ambiguity will also create uncertainty in the affected industries and States, which some are liable to use to justify inaction. It is not uncommon for this kind of litigation to take years to work its way through the courts and appeals process.

Year 3: Extensions

While the matter plays out in the courts, States will begin designing their implementation plans for how they will achieve their target. U.S. EPA has proposed States submit their plans by July 2016, with an option for a one year deadline extension if needed. Additionally, if a State proposes partnering with other States, such as part of a regional emissions trading system, they can have a two year extension, into 2018. So, it seems unlikely we will see the regulatory development process fully completed before the next Presidential administration takes office.

Year 4: Approval

USEPA is putting no restrictions on what policy measures State plans may chose, including building new nuclear plants, implementing a carbon tax, or joining a regional emissions trading system. Once a State has submitted a plan, USEPA will take about a year to approve or deny it. Plans will be approved or rejected based on an assessment of their likelihood of achieving their specified target. It is as of yet unclear how EPA will decide this question. And if a plan is rejected by USEPA, the result may be more negotiations, delay, and potentially litigation.

Year 5: Resistance

Some States may refuse to submit a plan by the formal deadlines (including extensions and lengthy negotiations), in which case the USEPA would then be expected to use its authority to begin implementing its own package of measures in the State for achieving the specified targets, an approach that would almost certainly be challenged in court. USEPA has not yet expressed what the process of developing and implementing a plan for a resistant State would look like.

Year 6: Execution

States must begin implementing and complying with their approved plans in 2020. A State could also develop a plan, get it approved by USEPA and then simply fail to follow through in implementing it, setting up a conflict with USEPA and potentially leading to years if not decades of political and legal fighting.

What about the politics?

Predicting the politics around this new proposed rule is more art than science. There are still many unanswered questions regarding how public attitudes will change over the next few years and how State plans will be evaluated by USEPA.

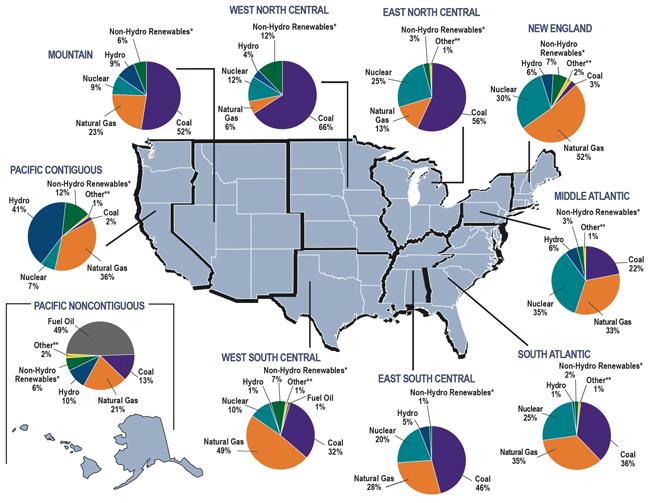

To get a sense of the domestic politics in the States, and which ones will likely fall into the resist or delay category, it is necessary to understand the geographic diversity in the U.S. generation mix. Unsurprisingly, the most resistance will likely come from States heavily reliant on coal.

Overall, the combination of the federalist regulatory process and the high degree of flexibility USEPA has given to the States to minimize their objections is likely to result in a messy and complex multi-year and multi-faction battle that seems almost sure to continue into the next President’s administration. A new President will take office in January 2017, and although a President cannot unilaterally repeal a final rule, they can weaken or slow down the implementation of a regulation while it is still being established.

Internationally, it will be interesting to see how Obama’s actions impact negotiations over global action. Initial public reactions from those gathered in Bonn this week for the latest round of UNFCCC negotiations indicates guarded enthusiasm, Yet, skepticism of the USA runs deep in the international community following the American failure to ratify the Kyoto Protocol or pass cap-and-trade legislation following Obama’s 2008 election. Although the EPA proposal seems to have already relaxed some of the stored-up tension over U.S. inaction on climate, in the longer term, it is still unclear whether this new proposed rule will really shift the dynamic in the international negotiations and increase the probability of a new global deal in Paris in 2015.

Another encouraging sign is that China is increasingly taking its own air pollution problems serious, which along with the potential to earn popularity points in the international stage by addressing GHG emissions in parallel with other air pollutants. My default position continues, though, to be skeptical that we will see progress at the international level. I hope to be surprised.

Skepticism aside, there is merit in noting the media-shift in attention this week on U.S. action on climate change both domestically and internationally. An interesting observation is that the automotive fuel efficiency standards, put in place by Obama in 2012, are forecast to reduce emissions about the same amount or more than this new power plant rule. Yet, this earlier regulation received far less attention. Politically, the expectation is that policy makers must address the burning of coal in a major way if they are to be seen as serious on climate change.

And so, despite my instinctive pessimism, I do think this is a big deal. I have some, albeit limited, hope that this new rule will push a large number of States to implement serious climate policies while also breaking the logjam in the negotiations at the international level.

Comments