When performing greenhouse gas (GHG) accounting work, such as preparing an emissions inventory or assessing an emission reduction project, you will, at some point, need to apply expert judgment. You may need to make assumptions to fill gaps in activity data or modify an emissions estimation methodology to account for process conditions not anticipated by a default methodology or emission factor.[1]

Unfortunately, no guidance document anticipates every possible technical issue. It is during these moments that you should refer to GHG quantification and accounting quality principles.

It is easy to forget about something so fundamental as quality principles. Or worse, dismiss such high-level principles and treat them as one of those inane posters with a person climbing a mountain above an inspirational word. Yet, we all should take time with each estimation effort to consider quality principles. They are genuinely useful as a touchstone to steer and justify our expert judgments.

It is easy to forget about something so fundamental as quality principles. Or worse, dismiss such high-level principles and treat them as one of those inane posters with a person climbing a mountain above an inspirational word. Yet, we all should take time with each estimation effort to consider quality principles. They are genuinely useful as a touchstone to steer and justify our expert judgments.

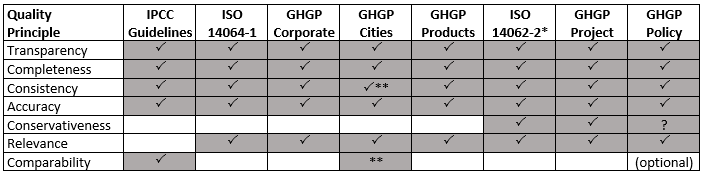

However, when you do spend time with these quality principles for GHG estimates, you begin to notice that there are discrepancies in which are applied and how they are defined across protocols, standards, and guidelines (Table 1). Do you know why these differences exist? Is there a reason they are defined differently, or is there a problem here?

The answers to these questions may be surprising. I would especially like to call out one deep-rooted and corrosive problem that originates from one missing principle. But, before I address this mystery of this missing principle, let us review Tables 1 and 2 and the state of GHG accounting principles across foundational guidance documents.

Table 1: Quality principles included in select major GHG accounting references (Table 2)

* Adopted by most voluntary GHG offset programs (e.g., Verified Carbon Standard)

** Does not distinguish the concept of comparability across emission inventories, but instead blurs the concept with time series “consistency” for an individual inventory.

? This GHG Protocol reference is equivocal as to the inclusion of “conservativeness” as a principle. It is listed separately from other principles in a text box.

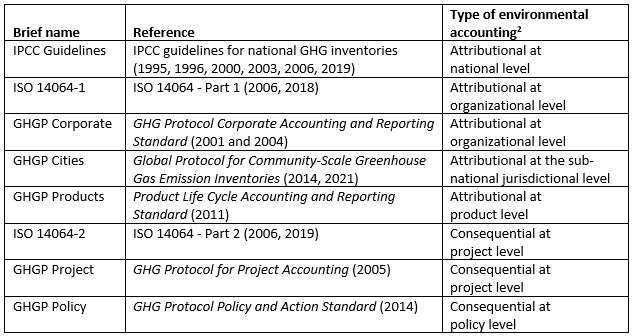

Table 2: Details on select major GHG accounting references [2]

Note: See Annex for text on each principle defined within these references.

The most likely candidate for a founding document within the GHG accounting field is the IPCC Guidelines for National GHG Inventories, which has been revised and expanded numerous times (1995, 1996, 2000, 2003, 2006, 2019). Over these years, along with parallel negotiations on the UNFCCC reporting guidelines for Parties, IPCC authors have achieved consensus on a set of precisely defined quality principles that should be familiar (linked here if you need a refresher).

Two decades ago, I coined the abbreviation TACCC as a catchy mnemonic for the training of national inventory review experts under the UNFCCC. The first letter was intentionally given as “T” for transparency, as it should be seen as a meta principle. Without transparency, none of the other principles can express themselves.[3] So for good reason, all major GHG accounting protocols, standards, and guidelines include this principle (see Annex for exact definitions of all principles from each reference).

Similarly, all these protocols, standards, and guidelines follow the IPCC’s and UNFCCC’s good practice lead for making judgments and include the principles of “A” “accuracy”, “C” “completeness”, and time series “C” “consistency”.[4] These are each unarguably sound principles to aspire to regarding the quality of GHG emission and removal estimates.

You will note, though, that this discussion is still missing one “C” from my abbreviation—our mystery principle. IPCC includes this “C”, but why have most of the other major GHG accounting guidance documents neglected this principle? Before addressing this mysteriously missing “C”, I am going to jump to two other principles found in other protocols and standards, yet not listed in the IPCC guidelines.

An interesting addition you may encounter when using some GHG accounting protocols and standards that involve consequential environmental accounting methods is the principle of estimation “conservativeness.” (For an explanation of the distinction between consequential and attributional methods read this before continuing). On the surface, the principle seems reasonable when quantifying GHG emissions reductions benefits. You typically do not want to over-credit the estimated impact of an intervention. Yet, logically, there is an incongruity between this principle and “accuracy.” The practical application of conservativeness entails the intentional biasing of quantitative results such that they deviate from the most accurate point estimate (i.e., which is statistically unbiased). Most of these consequential protocols and standards at least acknowledge this incongruity. And so, conservativeness is not a mystery “C” principle.

I would argue that rather than specifying “conservativeness” as a distinct GHG accounting principle—thereby placing two principles in open conflict—that it should be addressed as a policy design consideration within each GHG program or regulation (i.e., whether, how, and to what magnitude conservativeness is integrated into specific rules and methodologies). It can then be embodied in the program’s rules and methodologies in keeping with the intended users’ needs and expectations. Instead, the combined principles of “transparency” and “accuracy” should already be understood to require the open disclosure of uncertainties regarding the quantification of GHG emission reduction impacts. “Conservativeness” also stands out as an exceptionally awkward data quality principle. Holding all other factors constant, all other principles represent characteristics one should strive to maximize (e.g., more accuracy and completeness is good). In contrast, more and more “conservativeness” is not an objectively good characteristic for data to exhibit. Instead, you want just the appropriate amount of conservative bias in estimates, which in some cases may be none.

The principle of “relevance” is included in most major GHG accounting protocols and standards, but not in the IPCC Guidelines. On first inspection, this principle seems obvious. Of course, we do not want our GHG emission estimates to be irrelevant. Why would you go to the effort of preparing an emissions inventory or quantifying an intervention’s emission reduction impacts if the resulting data were irrelevant to the intended users of those results? So, why have these other protocols and standards decided it was necessary to add this seemingly obvious concept while the IPCC did not? Each of these other references attempts to provide generic and flexible guidance for any application of their targeted type of environmental accounting data. And in doing so, are vague as to exactly how the resulting estimates will or should be used. This ambiguity does not exist within the IPCC Guidelines, which have a well-understood application—compliance reporting of GHG emissions under international treaties. The relevance of the IPCC Guidelines is, by design, obvious. In contrast, it is only hoped that the data produced under these other protocols or standards will find constructive applications. I would argue that a well-constructed protocol, standard, or guideline should also, by design, be relevant by more precisely specifying how the resulting estimates produced under it are to be used. The serious problems arising from these application ambiguities are unlikely to be compensated for by reminding users that they should avoid relying on irrelevant data. If I could use my magic wand, I would erase “relevance” from being a quality principle. Unfortunately, it is all too familiar and reminds me of our historic use of “real” as a meaningless yet feel-good carbon offset quality criteria.

Now, finally, let’s come back to our mysteriously missing principle—“C” “comparability.” Why is it so often missing?

It is odd to imagine any proper “standard” that does not have as its fundamental purpose establishing practices that produce comparable results. Is that not the core purpose of standardization—replicable results that can support comparability (i.e., interoperability)? Put simply, by comparable we mean that the emission estimates produced for an entity (e.g., a facility, company, city, country, project, policy, or product) can be compared to estimates produced for other entities within the same accounting system boundaries. The meaning of this principle is especially germane for attributional environmental accounting methods, as they should produce emission estimates for a population of entities that sum to the system-wide total.[5] The absence of an explicit principle calling for comparable results in the application of GHG Protocol and ISO references is remarkable! For example, there are numerous uses of corporate GHG inventory reports that are contingent on estimates across companies being comparable. Specifically, the entire proposition of using reported corporate disclosures to inform investor and other stakeholder decisions presumes disclosures are comparable. Yet, the protocols and standards used for disclosing do not even aim for it, much less come near to achieving it. Can the design of a protocol or standard not pursue the production of comparable estimates and still be environmentally meaningful for decision-making? What logic justifies the enormous attention given to preventing double counting between corporate emission inventories that are not comparable in the first place? If we agree that climate actions will suffer if built on misleading GHG accounting, then we need more precision regarding the application of each standard. Policy and program neutrality is an illusory characteristic in a standard. It is unrealistic to expect a useful “standard” to be so widely applicable that even the limits of that applicability are not known. Ironically, out of this group, it is only the IPCC guidelines that foster standardization, while these other protocols and standards are better labeled as flexible guidance appropriate to a range of GHG accounting applications. I argue that the absence of “comparability” offered by these other protocols and standards is at the root of very serious GHG accounting missteps and problems. I will properly explore these problems in an upcoming post on how to better define attributional GHG accounting.

In the context of consequential environmental accounting methods, “comparability” is a more nuanced concept. It is desired in contexts where a policy or other decision involves a range of GHG mitigation options. The impact assessment of each option should be comparable to support project, policy, or action decision-making. But you would not expect, or even necessarily desire, comparability of impact assessments across totally different decision-making contexts. So, the principle applies within the bounds of comparing a single mitigation activity (e.g., narrow, such as for one emission source on a single site) or policy (e.g., broad, such as nation-wide building sector actions).

I hope drawing your attention to these discrepancies in principles has been thought-provoking, despite the seemingly mundane and pedantic nature of the topic. Like many professions, our deepest intentions are found in the principles and norms we advance in our work. As you may suspect, I favor the principles and definitions stipulated in the IPCC guidelines. They are the most thoughtfully, discretely, and carefully elaborated. Admittedly, looking back on history, I think my little mnemonic device has held up well. But we have some work to do still with the other GHG protocols and standards out there. Each of them would be wise to reconsider whether they have sufficient justification for augmenting or diverging from IPCC good practice. I for one, do not find any.

Annex: Data quality principles from major GHG accounting protocols, standards, and guidelines

Acknowledgments

I am thankful for the insightful comments from and discussions with my colleague Matthew Brander (University of Edinburgh), Derik Broekhoff (SEI), Molly White (GHGMI), and Tani Colbert-Sangree (GHGMI).

[1] See IPCC guidelines for quantifying uncertainty using expert judgment, pg. 19 of https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/pdf/1_Volume1/V1_3_Ch3_Uncertainties.pdf [2] Typologies of environmental accounting frameworks are typically described by their methodological accounting approach and estimation boundary. To learn more about the distinction between attributional and consequential methods within the GHG accounting space, see: https://ghginstitute.org/2021/04/21/the-most-important-ghg-accounting-concept-you-may-not-have-heard-of-the-attributional-consequential-distinction/ [3] This higher level significance of transparency is illustrated by how some protocols duplicate the call for transparency in their definitions of other principles. [4] Unfortunately, many become confused with principle of “consistency”, which properly is limited to the concept of having a consistent time series of estimates across years or other frequency of analysis. This quality principle is directed internally at each estimate and/or inventory. Technically speaking, the objective is to have the time series trend for each emissions estimate or inventory to be statistically unbiased. The principle does should not be confused with other colloquial uses of the term consistency such as conforming with certain accounting rules or the separate principle of comparability across emissions inventories for separate entities. [5] An upcoming blog post will delve deeper into this question.

Comments