Preface

This post continues a series (“what is greenhouse gas accounting?”) exploring conceptual issues in corporate greenhouse gas (GHG) accounting. If you have not read the series, all installments are available here – please do so; they provide important context for the issues explored here. Of particular relevance are Michael Gillenwater’s installments on allocation rules, responsibility and causation, as well as Michael’s blog post on whether Scope 3 emissions are “far greater” than Scopes 1 or 2.

This post and coming installments are focused on alternative accounting frameworks for what is currently (under the GHG Protocol) included under Scope 3 emissions accounting. We propose a bifurcation of approaches based on two main objectives of Scope 3 accounting:

- Communicating information about the GHG intensity of a company’s products and services, and

- Reporting on the effects of interventions that avoid emissions (or enhance removals) at sources and sinks within a company’s broader “value chain.”

What Scope 3 is good for, and what it is not

Before introducing these alternative accounting frameworks, it is worth considering why “Scope 3” exists in the first place. Given its logical inconsistencies and lack of coherence as a GHG accounting concept (compared to Scopes 1 and 2), what are the purported objectives of putting together a Scope 3 emissions inventory? The GHG Protocol’s Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Accounting and Reporting Standard (“Scope 3 Standard”) identifies four main objectives or “business goals” (WRI and WBCSD 2011, p.12):

- Identifying and understanding risks and opportunities associated with value chain emissions.

- Providing a basis for engaging value chain partners in GHG management (for example, to encourage suppliers to inventory their GHG emissions, and identify and prioritize which partners to engage with in managing emissions).

- Identifying GHG reduction opportunities, setting reduction targets, and tracking performance.

- Enhancing stakeholder information and corporate reputation through public reporting.

In the text that follows, we examine these (somewhat overlapping) goals in more detail, and whether Scope 3 accounting as it is currently practiced is “fit for purpose” in achieving them.[1]

Not fit for purpose (but a useful first step): (a) Identifying and understanding GHG inventory-related risks and opportunities, and (b) providing a basis for engaging with partners

The Scope 3 Standard notes that the process of developing a Scope 3 inventory can reveal GHG “hot spots” within a value chain. In other words, putting together an inventory might reveal inputs to production that are particularly GHG-intensive, or point to instances where the distribution, sale, and use of a company’s products or services are associated with significant GHG emissions. Identifying hot spots could, in principle, be useful for:

- Understanding a company’s potential exposure to certain kinds of regulatory risks (e.g., carbon pricing policies that might raise the cost of inputs or affect demand for a company’s products).

- Identifying potential changes in company procurement practices or opportunities for engagement with supply chain partners to mitigate emissions that might be worth exploring.

The problem is that most companies construct Scope 3 inventories using methods that provide only rough approximations of the emissions arising from major categories like “purchased goods and services,” “transportation and distribution,” or “use of sold products.”[2] For purchased goods and services, a common approach is to use spending data combined with economy-wide emissions factors derived from environmentally extended input-output (EEIO) models.[3] This “spend method” does not provide a specific estimate of the GHG emissions associated with the specific goods and services a company procures – which is what a more nuanced understanding of regulatory risk exposure, for example, would require.

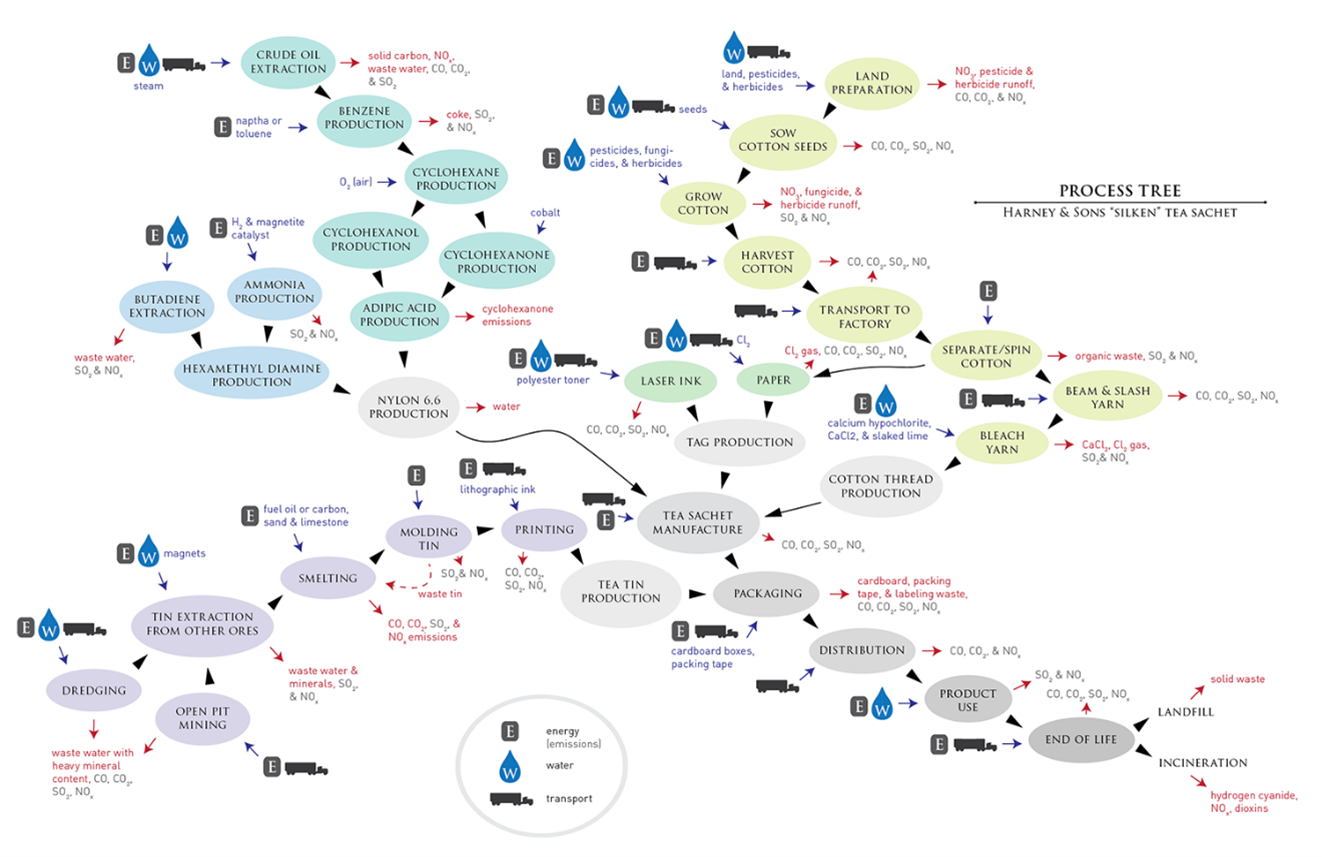

Furthermore, in terms of providing a basis for engagement with partners, these methods provide little insight into where specifically within a company’s supply chain emissions are released. According to one estimate, about one-third of supply chain emissions across different industries come from direct (“tier 1”) suppliers (Ballentine, 2024). The rest are associated with second, third, or “nth” tier suppliers further up the supply chain.[4] Few companies go so far as to produce value chain process maps of the sort depicted in Figure 1 for any, much less all, of their goods and services bought and sold. Yet this kind of mapping – which reveals relationships between primary producers, suppliers of intermediate goods and services, and downstream distribution, use, and disposal activities – is needed for all upstream and downstream goods and services to even start to yield a clearer picture of possible engagement opportunities, especially beyond the first tier.

In short, putting together a Scope 3 inventory is only a first step toward these objectives, and the numbers it produces are often only a rough guide to possible further exploration of risks and opportunities. That said, the process of developing something like a Scope 3 inventory could illuminate the breadth of emissions occurring throughout a corporate value chain and help in the initial identification of opportunities to lower emissions.

Not fit for purpose: (c) Setting reduction targets and tracking performance

The case is much weaker when it comes to using Scope 3 to set inventory emission reduction targets, and to track performance in achieving those targets. A big part of the problem here is, once again, the lack of resolution (granularity and specificity) in methods used to estimate Scope 3 emissions. In a survey conducted by SBTi, for example, 85% of respondents indicated access to data was a barrier to setting robust baselines for setting targets, an essential first step in tracking performance (SBTi 2023). Reflecting this challenge, 70% of responding companies had recalculated their inventory base year emissions (referred to in the survey as “re-baselining”) in the prior 5 years, with half of these recalculation efforts driven by methodological changes, including the use of different emission factor databases and calculation methods to improve accuracy. Ninety percent of respondents in this same survey indicated that setting “science-based” Scope 3 targets was “challenging.”[5]

Setting targets for reducing emissions when starting with only a rough approximation of base year emissions is at least a tractable challenge. After all, the most basic method for setting a target is to pick a number – e.g., identify what a 90% reduction in emissions from the base year would be – and use the result as a benchmark (however arbitrary). The fit-for-purpose problems arise when tracking performance toward this target. If a company changes structure, for example it sells off a division or adopts a different consolidation approach for constructing an inventory, then its existing base year inventory and target(s) may become obsolete. As explained in Michael Gillenwater’s installment N.3, tracking performance over time requires using consistent accounting boundaries and methods that produce a meaningful time series of emissions data. Recalculating the base year makes this goal more difficult (even if it is necessary to reflect changes) and, in practice, may require targets to be redefined.

The primary impetus for recalculating base year emissions, however, is not corporate restructuring, but the need to reflect revisions in the methods used to estimate Scope 3 emissions. Such revisions are often needed so that changes over time in Scope 3 emissions (due to a company’s efforts or otherwise) can be tracked at all. The “spend” method, for example, is unable to capture the real-world dynamism of value chains or the effects of many actions companies could take that – all else equal – might result in a lower GHG inventory, e.g., changes in procurement practices to favor lower-carbon inputs to production within the same “spend” category.[6] Using a spend-based approach to estimate Scope 3 emissions means that only reduced spending will observably reduce emissions.[7] However, if a company adopts new methodological approaches to replace low resolution methods like the spend-based approach, this often necessitates recalculation of base year inventory emissions.

However, the problems go much deeper than imprecise quantification methods. Even if highly accurate process-based data were used to construct a company’s entire Scope 3 inventory, we would still be left with a large “signal to noise” issue: the effect of a company’s actions within its value chain to lower emissions (i.e., signal) could be easily overshadowed by other factors affecting dynamic and expansive value chains (i.e., noise). Changes in emission inventories can occur due to multiple factors, many of which may be beyond the control of the reporting entity, or are otherwise unrelated to any interventions the entity makes to reduce inventory emissions. This is particularly applicable to indirect emissions, although it is true regardless of the scope involved. A company that changes its production processes to reduce direct, Scope 1, emissions intensity could see its Scope 1 emissions continue to rise if it is also expanding total production volumes. This makes it difficult – using inventory accounting – to communicate both the relative ambition of the company’s actions, as well as its progress in achieving them.

The problem is exacerbated when a company’s potential influence over inventoried emissions is limited (or even non-existent), and/or where changes in inventoried emissions can be caused by a multitude of exogenous factors. This is particularly the case for much of what gets counted under Scope 3 inventories. Under Scope 3, indirect emissions may be assigned multiple times to many different actors, and may occur (or are imputed to occur) over many years. While any single company may have the potential to “influence” these emissions in some way (even out to “nth” tier of suppliers), their degree of potential influence compared to other variables is often dilute (i.e., a weak signal-to-noise ratio). Scope 3 inventories lack the specificity and granularity to capture the effects of discrete interventions a company might make to progress toward inventory reduction goals by lowering the emissions of supply chain partners, a fact that perversely discourages engagement.[8]

This creates an awkward circumstance for setting targets. Implicit in any emission reduction target, for example, is the idea that reaching the target will require some level of effort on behalf of the target-setter. Yet, in the extreme – even if companies expended enormous effort to collect representative process-specific data from suppliers – they could in principle set targets for reducing Scope 3 emissions that simply align with what they expect to be exogenous changes in the emissions intensities of those suppliers (perhaps due to their supplier’s efforts to mitigate emissions, voluntarily or in accordance with government regulation). Conversely – and closer to what we see currently practiced under initiatives like the SBTi – companies may set “science-aligned” targets that they have no realistic means of achieving through their own efforts.[9] Perhaps unsurprisingly, 67% of respondents to the SBTi survey identified lack of confidence in their “ability to deliver scope 3 decarbonization” as a barrier to setting targets (SBTi 2023).

In short, the lack of precise metrics and the misalignment of inventory accounting with tracking the effects of a company’s interventions (exacerbated by the sheer breadth and “multi-counting” of emissions within Scope 3), make Scope 3 inventories ill-suited to fulfill target setting and performance tracking objectives.

Not fit for purpose: (d) Enhancing stakeholder information through public reporting

For the same reasons that Scope 3 inventories do not work well for target setting and performance tracking, they are also a poor metric for informing stakeholders. Without additional context, for example, a generic Scope 3 target will communicate little about a company’s relative ambition. The methods used to estimate Scope 3 emissions (along with “re-baselining” challenges), and the inability of Scope 3 inventories to reflect the aggregate effects of a company’s actions or interventions, mean that changes in Scope 3 emissions over time communicate little about what a company has actually achieved.

These issues are exacerbated by another weakness of the current practice of corporate GHG inventory accounting: lack of comparability between companies. A separate post in this series dissects the issue of comparability in detail. Suffice it to say that, for Scope 3, a lack of comparability is an even greater challenge than it might be for Scopes 1 and 2, given the diversity of methods companies may use to construct a Scope 3 inventory and the significant flexibility and ambiguity companies face in identifying value chain accounting boundaries and reporting emissions (even when following the GHG Protocol’s Scope 3 Standard). In summarizing the results of its own survey on Scope 3 emissions, the GHG Protocol notes that, according to many respondents, “the optionality and flexibility built into the Scope 3 Standard by design makes it challenging or impossible to normalize or make comparable GHG inventory results between companies, including for developing industry-specific or comparable KPIs” (WRI and WBCSD 2024, p.4) – with “some respondents” pointing out that “the non-disclosure of required or optional information makes it impossible for readers to compare inventories between companies” (WRI and WBCSD 2024, p.67).

To meaningfully inform stakeholders about the effects of actions that companies may take to address GHG emissions occurring within their value chains – and to assess the relative ambition of those actions – alternative accounting frameworks are needed. Such frameworks must lead companies to provide meaningful data related to the objectives that Scope 3 accounting is intended to enable, namely: (1) informing procurement decisions by different firms within sectoral value chains; and (2) consistently accounting for the effects of specific types of interventions that companies may undertake to avoid emissions within (segments of) their value chains.

Aligning “value chain” GHG accounting with discrete objectives

A key stated objective of Scope 3 accounting is to enable companies to effectively “manage” greenhouse gas emissions associated with their value chains. However, it is not always clear what “management” entails (or should entail) – aside from nominally reducing a company’s Scope 3 inventory. As discussed above, a Scope 3 inventory provides only a crude indication of where companies might effectively intervene to address value chain emissions, and a Scope 3 inventory itself is not an effective tool for setting targets, tracking performance, or reporting on the progress of a company’s efforts to reduce emissions (i.e., it does not produce a meaningfully sensitive emissions time series as Scope 3 emissions are affected by many exogeneous factors).

To design more effective alternative GHG accounting frameworks, it is necessary to first define the purposes of these frameworks. What precisely is it that we are asking companies to do when we ask them to manage Scope 3 emissions? Within the Scope 3 Standard, five broad kinds of actions are identified (Table 1). All these actions are nominally associated with “reducing Scope 3 emissions.” As Table 1 indicates, however, the effects of these actions could – in principle – be quantified in terms of:

- Reductions in allocated inventory emissions. Here, the term “reduction” means specifically that the action contributed to a lower quantity of allocated emissions in the period after the action was taken, compared to the period before the action was taken.

- Avoided emissions. Here, “avoiding” emissions means the action caused global emissions to be lower, compared to a counterfactual baseline in which the action was not taken.

Table 1. Five identified types of actions associated with “managing” Scope 3 emissions

| Type of Action | Examples | Could this reduce allocated emissions? | Could this avoid emissions? |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Using fewer inputs to produce a product or service | (Re)designing products in ways that require fewer materials or less packaging per unit | Yes, activity levels used to allocate emissions could be lower. | Possibly. Lower input demand could lead to fewer global emissions compared to the baseline (though rebound effects could partially counteract this). |

| (2) Switching to alternative types of inputs with lower GHG intensities to produce a product or service | Using wood as a building material instead of concrete | Yes, emission factor(s) used to estimate allocated emissions could be lower. | Typically, no. Global emissions, compared to the baseline, may differ only marginally (and could even be higher).* |

| (3) Switching to alternatives of the same type of input with lower GHG emission intensities to produce a product or service | Procuring concrete from suppliers whose production processes have lower GHG emission intensities | Yes, emission factor(s) used to allocate emissions could be lower. | Typically, no. Global emissions, compared to the baseline, may differ only marginally (and could even be higher).* |

| (4) Designing and/or selling products or services that have fewer downstream GHG emissions (e.g., associated with transportation, processing, use, and/or disposal) | Improving the energy efficiency (i.e., km/kWh) of sold electric vehicles | Yes, activity levels and/or emission factors used to estimate allocated emissions could be lower. | Yes, lower (or alternative) downstream energy and material demands could lead to lower global emissions, compared to the baseline.† |

| (5) Implementing mitigation measures (e.g., practice changes or technology adoption) with value chain partners that reduce their allocated emissions | Assisting transport providers to more quickly procure electric vehicles or replacing a natural gas heating system with an electric one at a supplier’s warehouse | Yes, activity levels and/or emission factors used to estimate allocated emissions could be lower. | Yes, mitigation measures may lead to lower global emissions compared to the baseline. |

| * This is because switching suppliers often leads to a simple reallocation of which suppliers serve which customers, rather than an absolute reduction in activity and emissions compared to the baseline (there may, however, still be some marginal effect on supply). † Avoided emissions associated with lower-emitting product/service designs are sometimes referred to as “Scope 4.” We will address this misconceived concept further in future installments. |

|||

The GHG Protocol Scope 3 Standard cites all five types of action as potential ways to reduce Scope 3 emissions. However, they will only (appear to) do so if methods used to quantify Scope 3 emissions are specific and sensitive enough to capture their effects.

This is the crux of the issue. The current lack of sensitivity in prevailing Scope 3 quantification methods has prompted proposals for alternative approaches that would enable companies to claim to have reduced their Scope 3 emissions – even if the effects of actions are not reflected in their physical Scope 3 inventory. Proposed alternatives include, for example, using market-based approaches to allocate emission factors associated with a particular activity or input, in lieu of (or as a proxy for) physically switching suppliers or implementing mitigation measures (actions 2, 3, and 5 from Table 1). An example of this approach would be the purchase of sustainable aviation fuel attributes used to claim lower air-travel-related Scope 3 emissions despite no physical change in the emissions released from planes on which the entity’s personnel or goods travel. This is problematic if the goal is to allocate emissions within corporate inventories (see more detailed reasoning and further examples in Installment N.4).

Other proposals would allow companies to calculate the emissions avoided by interventions they make in their value chains (action 5) and in some fashion deduct these avoided emissions from their Scope 3 inventory (regardless of traceability). An example of this approach would be an intervention by a chocolate company to lower the emissions of dairy farms (e.g., installing anaerobic digesters) that supply milk to the company. The company in its Scope 3 inventory would use a default factor for emissions from dairy products it receives, quantify the avoided emissions from their interventions to lower emissions on the dairy farms, and then deduct the avoided emissions from their Scope 3 inventory. Strictly speaking, this introduces a category error in corporate GHG accounting, by mixing consequential and allocational GHG metrics.

Rather than adopt these problematic accounting approaches to remedy deficits in Scope 3 emissions quantification, a more defensible approach would be to align accounting requirements with two separate purposes described below.

Purpose #1: Communicating consistent, comparable information about (changes in) the GHG emissions allocated to specific lines of products and services

For this purpose, an inventory accounting framework is needed (we’ll call this Framework #1) with enough sensitivity to capture the effects of actions identified in Table 1 in terms of reducing allocated emissions over time. For this, the inventory accounting framework would need to precisely and consistently allocate a limited set of emissions from direct and indirect sources for companies with the same product or service lines. These emissions would preferably be quantified using process-based methods for the major upstream or downstream emission sources related to the selected product or service lines.[10] Ideally, boundaries for allocating emissions would be comparable across analogous companies and the resulting emission estimates would be additive. As a simplified example, major process emissions occurring at cacao production sites would be included within the boundary of chocolate candy companies, for both a company that owns its own cacao farms (i.e., a direct emission source) and a company that does not own the cacao farms it sources cacao from (i.e., indirect emission sources). Yet, the inventory boundaries of chocolate candy companies would not extend further upstream to more distant suppliers. Overall, this allocation of emission sources would result in far more analytically tractable and far less expansive accounting boundaries than what is currently aspired to with Scope 3.

Purpose #2: Communicating the impact of mitigation actions undertaken within a value chain, but outside the accounting boundaries for the selected product and service lines included under Framework #1

Conceptually, a company’s GHG inventory, at a corporate level, could be constructed by simply adding together the allocated emissions of all its products and services, both consumed and produced. In practice, however, there are many contexts in which it is not feasible to develop allocated emission footprints for all of a company’s products and services (e.g., for a company that sells thousands of products), especially if this allocation is to account for an expansive life cycle. For some types of companies, and in some industries, developing product- or service-specific allocations may not be comprehensively feasible. To allow for companies to communicate the impact of mitigation actions within their value chain associated with products and services not included within Framework #1 an alternative type of GHG accounting framework is needed. This framework would be based on intervention-based (i.e., consequential) GHG accounting methods (Framework #2).

Framework #2 would quantify the impact of interventions that avoid emissions (or enhance removals) at sources or sinks located outside the improved, less expansive inventory boundaries of specific value chain segments (i.e., product or service lines). Of note, these interventions would still address emission sources that are conceptually within a company’s value chain. The wider boundaries of a company’s value chain (beyond those included within Framework #1) do not then need to be comparable or even precisely defined (indeed, this would be impossible given the many ways in which companies can be structured). Instead, it is the quantities of avoided emissions – associated with specific types of interventions – that would be comparable and additive.

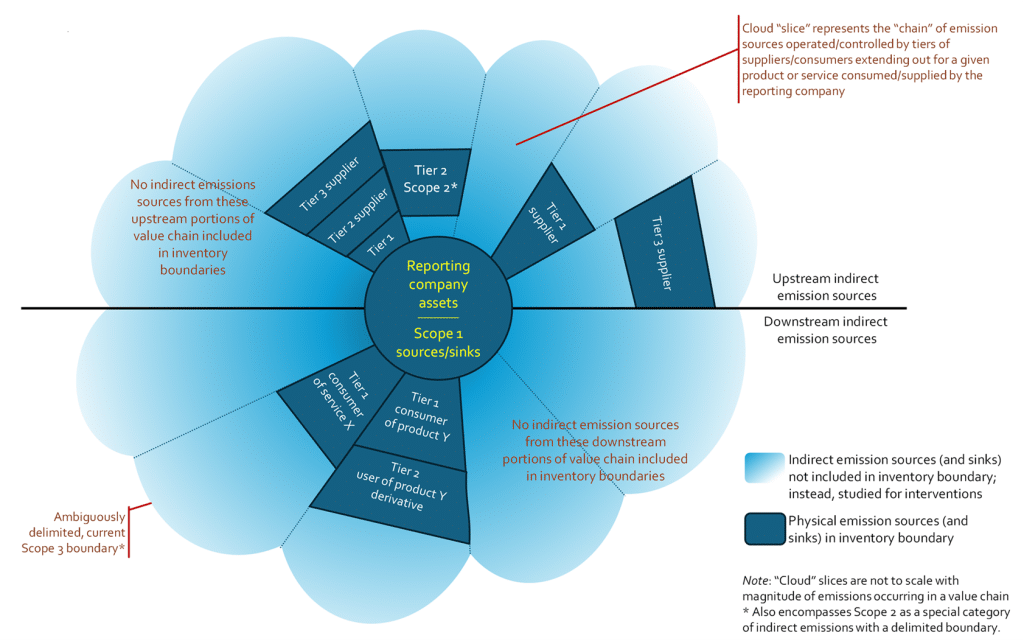

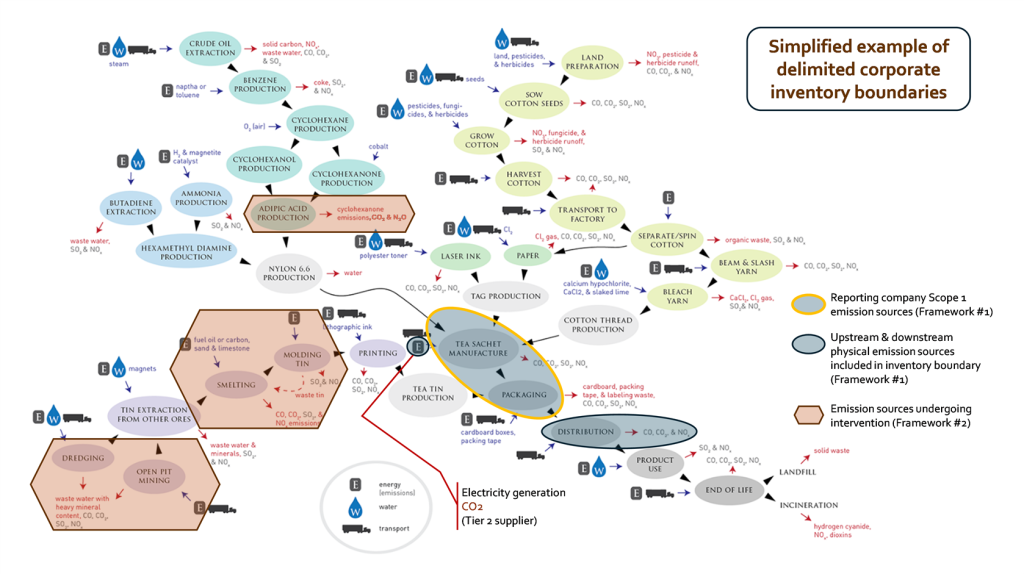

Figure 2 illustrates schematically how these two approaches might be deployed within the value chain of a hypothetical company.

Figure 3 provides a simplified example of more precisely delimited corporate GHG inventory boundaries (Framework #1) and an example of an emission source undergoing a mitigation intervention with avoided emissions accounted for under Framework #2. In place of the ambiguously expansive and overlapping boundaries of Scope 3, Framework #1 would target specific emission source and sink categories for a given industry or sector. The objective of this framework is to intentionally delimit corporate inventory boundaries to only major upstream and downstream sources and sinks that are selected to achieve comparability across similar product/service lines or across companies in the same industry or sector. Specifically, boundaries should extend far enough to allow inventories to be compared between a company that maximally outsources activities and one that maximally insources, such that results are unbiased regardless of corporate structure.

A new intervention GHG accounting framework

A key gap in corporate GHG reporting is for an alternative accounting framework that furnishes a comparable metric on the impact of substantial interventions that avoid emissions (or enhance removals) in corporate value chains – Framework #2. This new GHG accounting framework can supplement information provided through a reformed approach to corporate GHG inventory accounting (i.e., with boundary setting rules that more precisely and comparably allocate emissions) – Framework #1. And the effort currently spent on refining expansive Scope 3 estimates can be redirected to accounting for the impacts of value chain interventions that are aimed at cutting emissions at GHG sources or protecting and enhancing GHG sinks within the broader complex “cloud” of companies’ value chains (i.e., the area of Figure 2 outside a company’s allocated direct and indirect emissions).

The purpose of a parallel intervention GHG accounting framework is to consistently estimate over time the emissions avoided (or removals enhanced) by different types of interventions a company makes in its value chain. The results from this new intervention framework should not be interpreted as – or imputed to be – a “reduction” in a company’s Scope 3 emissions. Rather, they would be treated as a separate measure of the effects of a company’s intentional actions to address emissions occurring in its broader value chain. As such, they could also be subject to separate target-setting and performance tracking approaches. For example, a company could commit to making a collection of ambitious interventions that cumulatively avoid 100 tons of CO2 emissions each year from emission sources outside the company’s properly delimited – applying Framework #1 – allocational GHG inventory (but within its broader value chain). Such an intervention impact target would replace current targets for reducing expansive Scope 3 emissions, for which Scope 3 estimation methods do not meaningful track.

Now, anyone who has spent time developing intervention-based quantification methodologies – e.g., in the context of carbon crediting programs – will appreciate that it comes with numerous challenges. And undeniably, the development and application of an intervention GHG accounting framework will also entail challenges in establishing environmental integrity and practicality. However, unlike the status quo of Scope 3 reporting, a parallel set of two accounting frameworks has the potential to align each purpose of GHG accounting with the practical capabilities of each GHG accounting framework. The result would put corporate target setting, and performance tracking of emissions throughout corporate value chains, on much sounder footing and provide a credible reporting venue for companies to be appropriately recognized for the impact of their ambitious value chain interventions.

In further installments, we will explore the key elements of such an alternative intervention GHG accounting framework. Some of the key questions we intend to address in coming installments include:

- What purposes should a new intervention accounting framework satisfy and how should the framework vary to address different purposes?

- How should companies’ aggregate impacts across a range of interventions (i.e., how to ensure the quantification of impacts is comparable across interventions)?

- What types of cumulative intervention impact targets might companies and programs set?

- What are the eligibility criteria for interventions to credibly claim value chain intervention impacts? For example, should interventions with lengthy “causal chains” (i.e., mostly indirect impacts) be eligible?

- How should companies and programs account for market-scale interventions, such as those implemented through environmental commodity markets (e.g., sustainable aviation fuel certificates)?[12]

- Should the new framework apply to “beyond value chain” interventions (and if so, when and how)?

- Most critically, how should baseline scenarios, against which avoided emissions are established, be determined?

- What principles and rules guide who gets to claim intervention impacts (e.g., when multiple parties are contributing to an intervention)?

- What types of information should be reported by companies under a future intervention GHG accounting framework?

We welcome collaboration with others researching and writing on these questions. There is no time to waste, as the time for such an alternative parallel GHG reporting framework is long overdue. We acknowledge that adding additional GHG metrics will not be a panacea, but it does offer metrics that are far more fit for purpose by actually measuring over time what we want to track and encourage—the decarbonization of corporate value chains.

Click here to read all the posts in the “What is GHG accounting?” series

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the insightful comments from and discussions with Brad Schallert (Winrock) and Tani Colbert-Sangree (GHGMI).

Recommended Citation

Broekhoff, D. and Gillenwater, M., (2024). Is Scope 3 fit for purpose? Alternative GHG accounting framework[s] for intervention impacts. Seattle, WA. Greenhouse Gas Management Institute, October 2024. https://ghginstitute.org/2024/10/28/is-scope-3-fit-for-purpose-alternative-ghg-accounting-frameworks-for-inventories-and-intervention-impacts/

Endnotes

[1] See Michael Gillenwater’s separate installment N.2 for a general overview of possible functions and objectives of corporate GHG accounting, and which accounting forms are most appropriate to achieve them. [2] According to a survey on Scope 3 accounting conducted by the Science Based Targets initiative, “purchased goods and services” and “use of sold products” together represent more than 70% of Scope 3 emissions reported to the CDP’s reporting platform (SBTi 2023). [3] In SBTi’s Scope 3 survey, only 6% of respondents indicated they use any supplier-specific emission factors (SBTi 2023). [4] A further complication is that the terms “supply chain” and “value chain” are effectively misnomers, or at least fail to capture the complexity of possible interrelationships among firms and industries involved in producing inputs to any manufacturing process. Many “supply chains” are really “supply matrices” or “supply networks,” given the extent to which intermediate producers rely, for their own production, on the same cross-section of primary goods and service producers – a fact that is reflected in EEIO models. See Figure 4, for example, in Michael Gillenwater’s related post on allocation rules. See also Hearnshaw and Wilson (2013). [5] In a separate survey by the GHG Protocol, respondents also identified recalculation as a challenge for consistency in disclosure, baselining, and performance tracking (WRI and WBCSD 2024). [6] In SBTi’s survey, 59% of respondents cited inability to track progress in achieving targets due to lack of primary data as a major challenge. [7] Reduced spending can result from meaningful actions that reduce a company’s allocated GHG emissions, such as adopting more material-efficient production practices and technologies but is otherwise a blunt measure of performance. [8] As one respondent to SBTi’s survey noted, “Engaging suppliers is high effort and low reward – we are much better off directly taking action ourselves. All the guidance is about getting the numbers better and not action” (SBTi 2023, p.19). In this case, “getting the numbers better” means taking actions that nominally reduce Scope 3 (like reducing spending), while forgoing direct supplier engagement (which could have a more meaningful effect on global emissions). [9] As another extreme, these two scenarios could be one and the same – i.e., a company could set a “science-based” Scope 3 target that it expects to “achieve” simply through the anticipated actions of its supply chain partners (or in the case of a financial institution, the actions of companies in its investment portfolio). [10] The framework would look very similar to the delimited accounting boundaries for companies proposed in installment N.3. The specific indirect emissions associated with a product or service could be constructed using process maps like the one illustrated in Figure 1 (of this installment). The key is to ensure – at a product or service level – both comparability and additivity, as explained in installment N.3. [11] Note that some product or service line ‘slices’ in Figure 2 identify a Tier 2 or 3 supplier but do not include the lower number Tier suppliers (for these ‘slices’ the Tier 2 or Tier 3 supplier is not directly touching the “reporting company assets” circle in the center). This represents the situation in which for example a Tier 2 supplier provides an input to a product line and that input is superficially processed by the Tier 1 supplier and therefore not considered a significant emission source. [12] And what additional accounting rules are needed to address activity pools?References

Ballentine, R. (2024). Scope 3: what question are we trying to answer? Frontiers in Sustainable Energy Policy, 3. DOI:10.3389/fsuep.2024.1378390.

Hearnshaw, E. J. S. and Wilson, M. M. J. (2013). A complex network approach to supply chain network theory. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 33(4). 442–69. DOI:10.1108/01443571311307343.

SBTi (2023). Catalyzing Value Chain Decarbonization: Corporate Survey Results. Science Based Targets initiative. https://sciencebasedtargets.org/resources/files/SBTi-The-Scope-3-challenge-survey-results.pdf.

WRI and WBCSD (2011). Greenhouse Gas Protocol: Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Accounting and Reporting Standard : Supplement to the GHG Protocol Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard. World Resources Institute; World Business Council for Sustainable Development, Washington, DC]; [Geneva, Switzerland.

WRI and WBCSD (2024). Greenhouse Gas Protocol: Detailed Summary of Scope 3 Stakeholder Survey Responses. World Resources Institute; World Business Council for Sustainable Development, Washington, D.C. and Geneva, Switzerland. https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/2024-06/Scope%203%20Survey%20Summary%20-%20Final%20%281%29.pdf.

Cover image by @tchallioui via https://emojis.sh/emoji/supply-chain-process-YuMHVLMgaM

Comments